If you want to master the art of handling tough conversations, then “Crucial Conversations” is a must-read. This book will show you how to master the critical skills needed to stay calm and confident during tough talks. You’ll learn practical tools and strategies that will help you level up in leadership and communication.

Whether you’re aiming to improve your communication at work, manage personal relationships better, or resolve conflicts effectively, this book offers the guidance you need. In the following summary, we’ll highlight the key takeaways from each chapter, so you can understand the essential strategies and start applying them in your daily interactions.

📖 1. Summary by Chapter: Every chapter of “Crucial Conversations” explained in 5 minutes

First, you’ll get a quick overview of the key concepts and lessons you should know from each chapter of the book.

Chapter 1 Summary

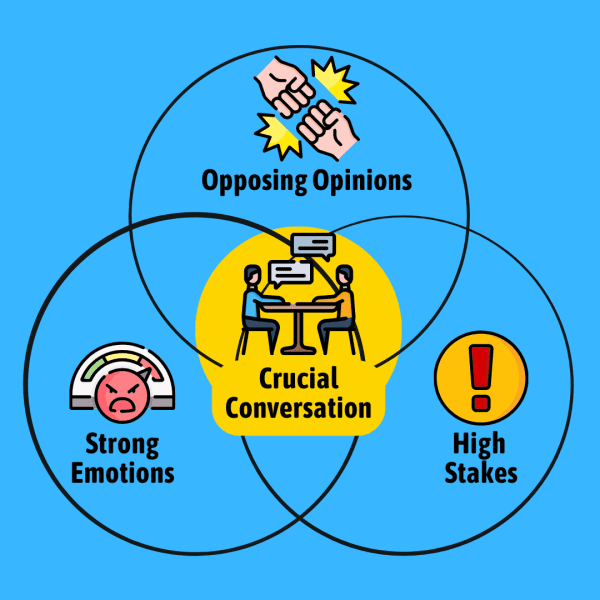

- A crucial conversation is when there are opposing opinions, strong emotions, and high stakes involved. They happen in important areas of our lives, like career decisions, job promotions, relationships, family matters, and community issues.

- When conversations matter the most, we often perform the worst because emotional stress triggers our fight or flight response, diverting blood to large muscles and away from parts of your brain responsible for higher reasoning.

- The authors claim that skillfully handling risky topics is THE key skill of effective leaders, supported by 20 years of their research involving 100,000 people.

Chapter 2 Summary

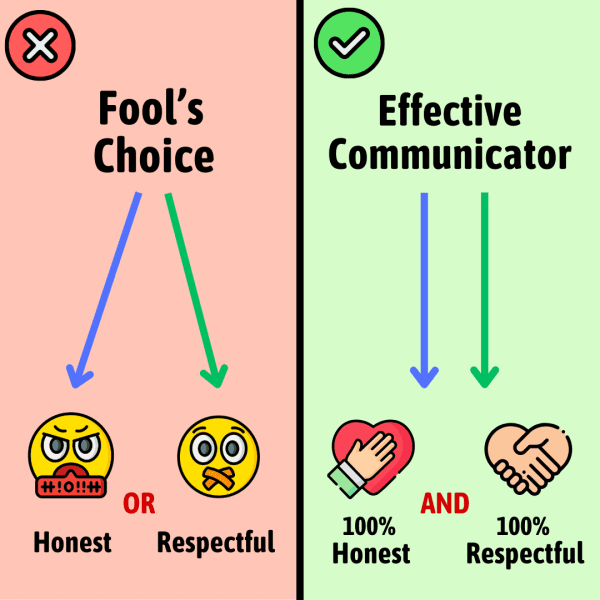

- The authors researched why some people are more effective and influential. They found that successful individuals, can address difficult topics by being 100% honest AND 100% respectful at the same time. This approach avoids the common mistake, called the Fool’s Choice, where people think they must choose between being honest or being respectful, often resulting in silence or hurtful comments.

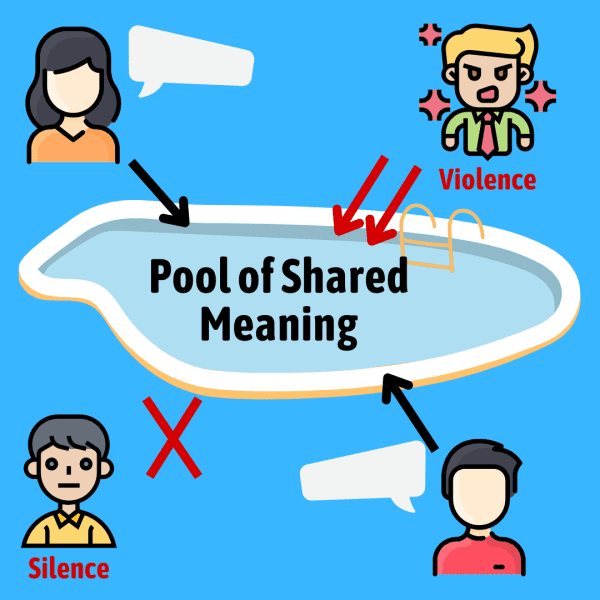

- The key to crucial conversations is creating a safe environment where everyone feels comfortable sharing their thoughts, even if those thoughts are controversial or different from the majority. The more people contribute to the pool of shared meaning, the better and smarter the final decision will be.

Chapter 3 Summary

- Start with heart means focusing on your true intentions before starting a conversation. Make sure your motives are right and other people will be less likely to get defensive, because they can feel the place you’re coming from.

- Stay focused on what you really want. When emotions run high, we often forget our main goals and try to win or punish the other person. Ask yourself: What do I want for me, for them, and for our relationship?

- Avoid the Fool’s Choice by looking for “the elusive AND.” For every crucial conversations, get clear on both what you want AND what you don’t want. For example, “I want to talk to my spouse about this issue… AND avoid making them feel criticized or guilty.”

Chapter 4 Summary

- Pay attention to both the content and conditions of conversations to spot safety problems early on. Notice not just what is being said but also how people are reacting, like getting quiet or looking upset. When people feel unsafe, they tend to resort to either silence or violence.

- Spot when a conversation becomes crucial by recognizing symptoms that are physical, emotional, or behavioral—like you having a dry mouth, feeling charged, or beginning to raise your voice.

- Understand your style under stress by reflecting on past difficult conversations. Notice if you withdrew from the dialogue or attacked the person instead of the issue. This helps you recognize future crucial conversations quickly.

Chapter 5 Summary

- If someone feels unsafe in a conversation, pause and rebuild safety, then continue talking.

- People feel safe when there is mutual purpose and mutual respect. To create mutual purpose, make sure they know you care about their needs. For mutual respect, treat others with dignity, because we are all human beings flawed in our unique ways.

- Rebuild safety by:

- Apologizing if needed,

- Asking why they want something to help you find a common solution, and

- Contrasting to clarify misunderstandings. Contrasting is a “don’t/do” statement where you begin with clarifying what you don’t mean to say, then explain what you do mean.

Chapter 6 Summary

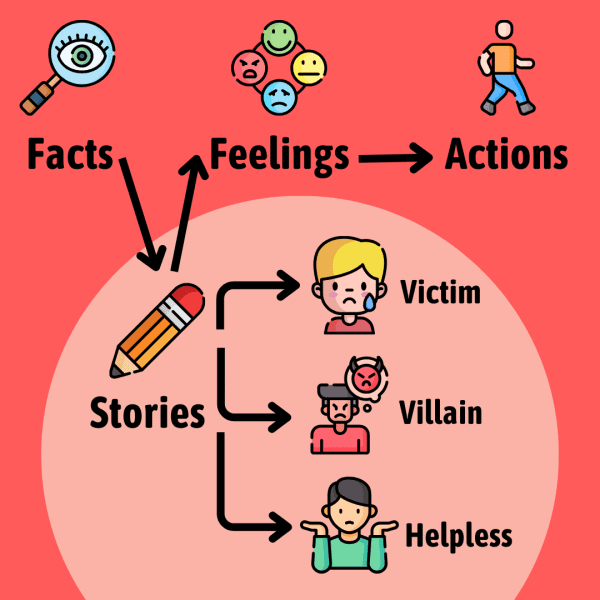

- Emotions come from the stories we tell ourselves about what we see and hear. We can control our reactions by changing these stories.

- Interpret events differently to change your feelings. For example, if someone dominates a meeting, consider they might be nervous instead of thinking they find you incompetent.

- Question your stories by asking if you’re seeing yourself as a victim, blaming others as villains, or feeling helpless. Look for your role in the problem and consider other possible stories that fit the facts.

Chapter 7 Summary

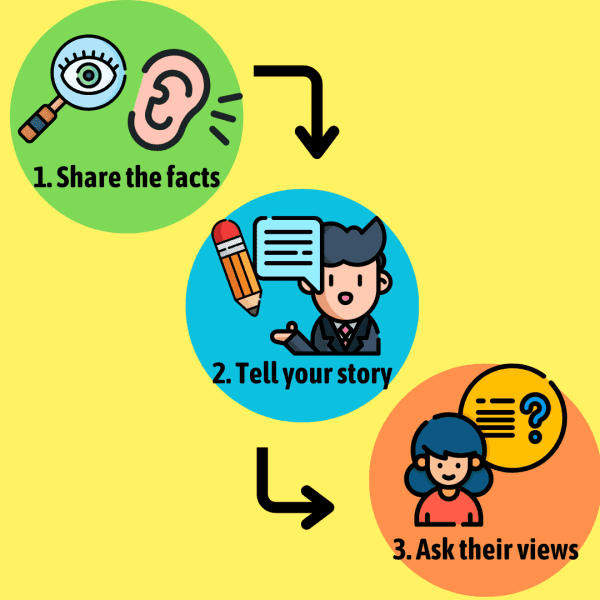

- When discussing sensitive topics, start with the facts. For example, if a wife finds a motel receipt and worries her husband is cheating, the best way to begin is by saying, “I found this receipt,” instead of making accusations.

- Then share your story, which is really your interpretation of the facts. Speak tentatively because this makes others more open to listening and considering your perspective.

- Ask for the other person’s viewpoint and encourage them to share their side. If they hesitate, you can guess what they may be thinking or play devil’s advocate to get the conversation going.

Chapter 8 Summary

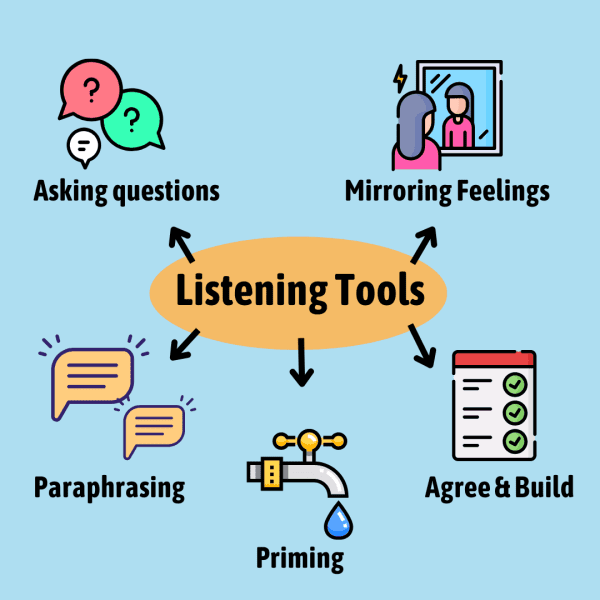

- Some strategies for listening are:

- Ask what’s going on,

- Mirror their emotions by stating how they look or act,

- Paraphrase what they said in your own words, and

- Prime by guessing what they may be thinking or feeling.

- To disagree while maintaining safety, use the ABCs: begin with points of agreement, build on their points by saying “yes, and…”, and compare differences respectfully instead of starting with saying they’re wrong.

Chapter 9 Summary

- Decide how to decide: Sometimes the decision-making process is straightforward, like when there is a clear line of authority (e.g a parent or manager). In many other situations, how the final decision is made must be part of the discussion process.

- Four ways to make decisions:

- Command is following external guidelines, like the boss guiding engineers to follow safety standards,

- Consulting is seeking advice from an expert,

- Voting is best when choosing among a few good options, and

- Consensus for complex decisions needing strong unity, though it’s time-consuming.

- Make assignments: Specify who does what by when, and how follow-up will occur.

Chapter 10 Summary

- This chapter offers advice on applying these tools in specific tough scenarios like dealing with harassment at work, an overly sensitive spouse, or unreliable coworkers. There are no new major concepts.

Chapter 11 Summary

- This chapter is a review of book’s key principles, emphasizing learning to look (for signs of silence/violence that indicate a crucial conversation has begun), and making it safe (especially by asking for their input).

In the bestselling book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, author Stephen Covey wrote, “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.” Essentially, that means if we want to have influence over other people, we must first be open to being influenced by them, by sincerely trying to see from their point of view. That author wrote, “Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply.” And, as you’ll see, this is a core principle of Crucial Conversations too.

What is a key practice of people who are skilled at dialogue?

Agree with others

Avoid conflict

Change the story

Make it safe

Now, let’s move on to a deep dive into the best practical ideas and key takeaways in this book…

❤️ 2. Start with Right Intentions: Begin a crucial conversation being 100% honest and 100% respectful

To handle crucial conversations effectively, begin with the right intentions or motives. Do this by focusing on what you REALLY want for yourself, the other person, and your relationship. Avoid the “Fool’s Choice” of thinking you can be either honest OR respectful—strive for both.

When you’re in a difficult conversation, it’s essential to start with the right intentions in your heart. This means checking your motives before you even begin to speak.

You see, when emotions run hot, we can easily lose sight of our true goals and get caught up in trying to win the argument or, worse, punish the other person. Partly, this is because of the way evolution has wired our brains—when stressed blood is diverted towards large muscles and away from our brain’s complex thinking area. Partly, it has to do with our culture’s emphasis on winning.

To stay focused, ask yourself: What do I want for me? What do I want for them? What do I want for our relationship?

Consider the example of Kevin, one of several VPs in a company. The CEO of the company tended to get angry when challenged, so when he proposed a bad idea for a new office location, everyone else kept quiet. However, Kevin approached the situation differently. He politely and calmly explained how the CEO was violating his own past rules. Kevin avoided the “Fool’s Choice” by being both 100% honest and 100% respectful, leading to a productive outcome for everyone.

To avoid the “Fool’s Choice,” look for “the elusive AND.” This means asking yourself how you can achieve both what you want AND avoid what you don’t want in the conversation. For example, “I want to talk about this sensitive issue with my spouse so we can find a solution everyone agrees with, AND avoid making them feel criticized while we’re talking.” By adding that second part of the statement, you’re putting the right motive in your heart to handle the conversation better.

What is the key to effective communication?

Being completely honest

Being absolutely polite

Avoiding uncomfortable topics

Being 100% honest and 100% polite

🛡️ 3. Make Sharing Safe: Tools for maintaining safety and encouraging everyone to contribute to the “pool of shared meaning”

To ensure everyone feels safe to share their ideas, watch out for signs of “silence or violence” and work to rebuild safety using tools like contrasting and mutual purpose. This helps increase the group’s collective intelligence by ensuring all voices are heard.

In any crucial conversation, the goal is to ensure that everyone feels safe enough to contribute their thoughts and ideas. This helps us create a “Pool of Shared Meaning,” where the group’s collective intelligence is enhanced by diverse perspectives. To achieve this, it’s important to recognize and address signs that someone feels unsafe.

When people don’t feel safe, they often resort to silence or violence:

- Silence can manifest as avoiding topics, understating true opinions, or even walking away.

- Violence, on the other hand, includes dominating the conversation, belittling others, or using hurtful comments. These reactions are often indicators that the person feels attacked or disrespected.

3 ways we can rebuild safety:

- Apologize if you’ve caused any pain or difficulty. A sincere apology shows that you’re willing to admit mistakes and focus on the greater goal.

- Contrasting is an amazing tool to clear up misunderstandings. This is a “don’t/do” statement where you first say what you don’t mean, then what you do mean. For instance, saying “I don’t mean to criticize you; I do want to help us find a solution…” can help clarify your intent.

- Mutual purpose is also crucial to establish. This is about making sure the other person understands that you care about their needs and wants, not just your own. For example, instead of criticizing a boss for being unreliable, you could start by discussing how you can help them achieve their goal of meeting deadlines faster… and use that as a bridge to help them understand your problem with them being unreliable.

Another way to find mutual purpose is by asking them WHY they want something, to see if you can determine their real needs and find another way to fill those needs with a mutual solution. For example, if one person wants a quiet night in while the other wants to go out to a noisy place, ask why. They might reveal they want to get away from the kids, leading to a compromise of going out to a quiet place.

This last idea is very similar to a core concept in the powerful negotiation book “Getting to Yes,” written by Harvard business experts. That book says to “focus on interests, not positions”— it emphasizes looking underneath people’s stated positions in a negotiation to find their real underlying interests.

Imagine two coworkers arguing about the best way to complete a project. One insists on using a specific software, while the other prefers a different tool. Instead of getting stuck deeper in their conflicting positions, they decide to explore their underlying needs. They find out one wants speed, and the other wants accuracy. They agree to use the fast software first and the accurate tool for final checks, meeting both needs effectively.

What is it called when you make a statement that first clarifies what you don't mean, then says what you do mean?

Contrasting statement

Conditional statement

Meaning statement

Mutual purpose statement

🧠 4. Stories Cause Feelings: Taking control of our emotional reactions by shaping the stories we tell ourselves

To manage your emotional reactions, understand that your feelings are shaped by the stories you tell yourself about what you see and hear. Avoid the “clever stories” that cast you as a victim, villain, or helpless person. Take control by remaining open to multiple interpretations of the facts.

When it comes to handling our emotions, it’s crucial to recognize that others don’t “make” us feel anything; rather, we create our own emotions through the stories we tell ourselves.

Most people think emotions follow the sequence of see -> feel -> act, but the true process includes a critical step: see -> tell story -> feel -> act. The authors of “Crucial Conversations” call this “The Path to Action.” This means our feelings are directly influenced not only from the facts we observe, but even more strongly by the stories we interpret from those facts.

For example, if a coworker dominates a work presentation, you might tell yourself a story that they think you’re incompetent, leading to feelings of anger or inadequacy. However, another interpretation could be that they are nervous and over-talking. Both stories are based on the same facts but lead to very different emotions and actions.

To take control, you can retrace your path to action by asking yourself what story you are telling. Observe your actions (silence or violence), then notice your feelings, and finally, identify the story behind them. Challenge this story by considering other possible interpretations of the facts.

The authors also tell us to avoid falling into the trap of “clever stories” which justify our behavior and relieve us of responsibility:

- Victim stories tell us: “It’s not my fault.” Ask yourself: “Am I ignoring my role in sustaining this problem?”

- Villain stories say: “It’s all their fault.” Ask yourself: “Why would a reasonable person act the way they’re acting?”

- Helpless stories say: “I couldn’t have done anything else.” Ask yourself: “If I really wanted to achieve the goal I claim to want what would I do?”

The problem of all these stories is they are incomplete, they are only part of the story. By questioning our clever stories and telling a more complete and accurate story, you can better manage your emotions and reactions, leading to healthier and more productive relationships.

What is the true sequence of the "Path to Action"?

See -> Feel -> Act

See -> Act -> Feel

See -> Tell Story -> Feel -> Act

See -> Feel -> Tell Story -> Act

🗣️ 5. Focus on the Facts: Share the facts first, then tell your story tentatively, and ask their view

To effectively begin a crucial conversations, start by sharing the uncontroversial facts of what happened, then tell your story tentatively, and invite others to share their perspectives. This approach encourages open dialogue and reduces defensiveness.

When trying to persuade someone, it’s crucial to start with the facts. Facts are less likely to be disputed and provide a solid foundation for the conversation.

For example, imagine a manager noticing an employee frequently arriving late to work. Instead of accusing the employee of being lazy with “You’re always late because you don’t care about your job,” the manager should start with the fact: “I’ve noticed that you’ve been arriving after 9 AM several times this month.”

Next, share your interpretation of the facts by telling your story, but do so tentatively. This means expressing your concerns or conclusions without appearing overly certain or dogmatic.

The manager might say, “I’m concerned because when you arrive late, it impacts our team’s productivity and morale.” By presenting it as a concern rather than an accusation, the employee is more likely to be open to the discussion.

Finally, ask for the other person’s perspective. Show that you are genuinely interested in hearing their side of the story. Encourage them to share their thoughts by asking open-ended questions like, “Can you help me understand why this is happening?” or “Is there something going on that’s affecting your arrival time?” This not only opens up the dialogue but also shows respect for their viewpoint.

Since the best way to start a tough talk is by focusing on the fact, not interpretations, which of the following statements should you use?

You're always late.

I noticed you arrived late.

You don't respect the schedule.

You must be lazy.

👂 6. Show Empathy: Practice active listening techniques like mirroring, paraphrasing, and priming

To understand the other person’s perspective, use listening tools like asking questions, mirroring by describing their emotions, paraphrasing what they said, and priming by guessing their thoughts. Finally, build on points of agreement and respectfully show how you differ, instead of starting with disagreement.

When engaging in crucial conversations, effective listening is vital to understanding and resolving issues. Here are five key tools for active listening:

- Ask: Begin by asking open-ended questions to understand the other person’s perspective. A simple “What’s going on?” invites them to share their thoughts and feelings without feeling pressured or judged.

- Mirror: Reflect the other person’s emotions and actions to show empathy and understanding, especially if their words and actions don’t align. For example, if they claim to be fine, but they look upset, you might say, “You look upset.” This encourages them to open up about their true feelings.

- Paraphrase: Summarize what the other person has said in your own words. This demonstrates that you are actively listening and ensures you have accurately understood their point of view. For example, “So, you’re saying that you feel overwhelmed by the workload?”

- Prime: When someone is hesitant to share, take a guess at what they might be thinking or feeling. This can help them articulate their thoughts. For instance, “Are you feeling stressed because of the upcoming deadline?”

- ABCs – Agree, Build, Compare: Start with points of agreement to create a positive foundation. Instead of outright disagreement, build on their points by adding your perspective. For example, “Yes, I see your point, and I think we can also consider…” Finally, compare differences respectfully by saying, “Here’s where I think we differ…”

Another great book on negotiation is “Never Split the Difference” by Chris Voss, a former FBI lead kidnapping negotiator. He says one of the most powerful negotiation strategies is “tactical empathy” and uses a tool called “labeling,” similar to mirroring.

For example, in one tense situation, three dangerous fugitives refused to come out of an apartment building. So for 6 hours, Chris and his FBI colleagues used labelling: “It seems like you’re scared of going back to jail”, “It looks like you’re scared we’ll start shooting if you open the door”, etc. This empathy helped calm them down, and they eventually surrendered.

Chris Voss wrote, “Research shows that the best way to deal with negativity is to observe it, without reaction and without judgment. Then consciously label each negative feeling and replace it with positive, compassionate, and solution-based thoughts.”

What does "priming" involve in a conversation?

Guessing their feelings

Giving advice

Making accusations

Asking directly

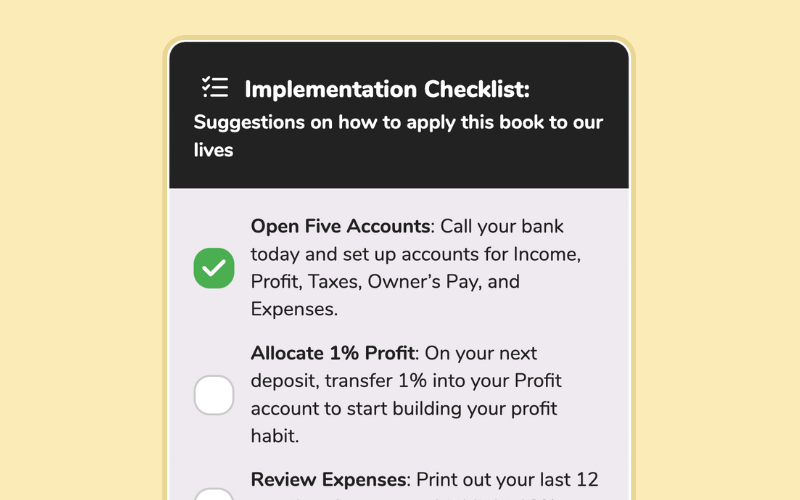

- Check Your Motives: Before a difficult conversation, write down what you want for yourself, the other person, and the relationship.

- Create Safety: Watch for signs of discomfort or defensiveness and take a step back to make it safe for the other person to speak.

- Clarify Intent: Use contrasting statements by saying what you don’t mean followed by what you do mean to avoid misunderstandings.

- Start with Facts: Begin crucial conversations by stating observable facts before sharing your interpretation or feelings.

- Use Tentative Language: Practice using phrases like “I’m beginning to think” or “It seems to me” to share your story without sounding dogmatic.

- Mirror and Paraphrase: During conversations, reflect the other person’s emotions and summarize their points in your own words.

Community Notes