📈 1. Keep It Simple with Index Funds: Instead of trying to “beat the market,” choose index funds—a simple, low-risk way to own the entire market.

Today, many of the most popular finance books are champions of index funds. I’m thinking of The Psychology of Money, The Simple Path to Wealth, Tony Robbin’s Unshakeable, and many more. These authors owe a great debt to John Bogle, who basically invented the idea of the index fund and created the first one through his company Vanguard. So let’s jump in!

Introduction Summary

The introduction gives an overview of the book’s core argument, showing how investing in low-cost index funds is a simple and smart way to grow your money without taking big risks.

- How index funds work: An index fund lets you own a small piece of every company in the stock market. This way, you share in the market’s overall growth, company profits, and dividends—without the risks of picking individual stocks or the high fees of actively managed mutual funds.

- The power of compounding: Over time, even a small amount of money put into a stock index fund can grow a lot thanks to compounding—with a 7% annual return, each $1,000 you invest can grow to $30,000 within 50 years. That’s better than the vast majority of investors who try to “beat the market.”

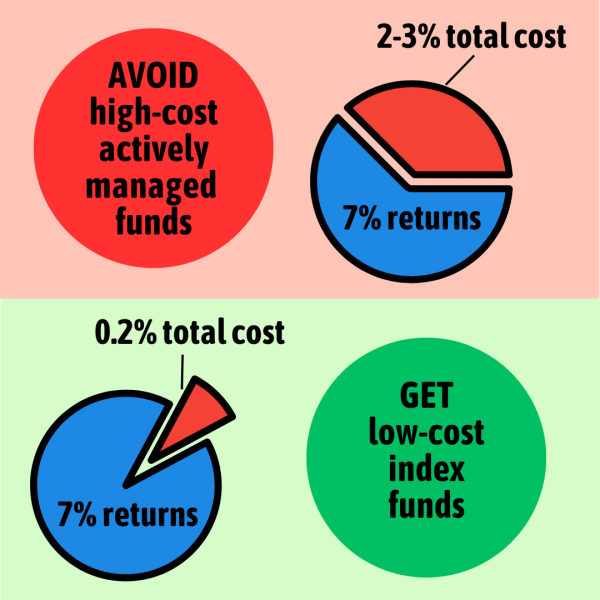

- Avoid Wall Street’s high fees: Traditional mutual fund managers of Wall Street makes billions from high fees and frequent trading, but that takes money out of your pocket. Many actively managed funds have a 2% “expense ratio,” which means annual fees. That doesn’t sound like much, but compounded over years, those fees take away a significant chunk of your wealth. Index funds keep costs low and eliminate unnecessary expenses.

- The index fund revolution: John Bogle created the first index mutual fund in 1976, starting a movement that transformed investing. Assets in index funds have skyrocketed from $28 billion to $4.6 trillion, proving this simple strategy really works.

Chapter 1 Summary

This chapter uses a simple story to show why most investors lose money when they try to beat the market instead of sticking to low-cost index funds.

- The story of Gotrocks: This is based on one of Warren Buffett’s letters. Imagine a family called the Gotrocks that owns the entire stock market and earns all its growth. Then, “Helpers” show up and convince some family members that they can make more money by picking specific stocks. The family begins paying fees for these advisors and consultants, which leads to frequent buying and selling—and results in higher taxes. Over time, the family’s share of the market’s growth shrinks from 100% to just 60% because of all these costs.

- Returning to common sense: A wise uncle steps in and says, “Stop paying fees and taxes. Go back to a simple, passive strategy.” As a group, investors can only earn the market’s growth minus the fees and taxes they pay. Active investing benefits financial intermediaries like stockbrokers and advisors, not investors. Most people would grow their money faster by avoiding these costs and sticking to index funds.

- Harvard uses index funds: Jack R. Meyer, who tripled Harvard’s endowment fund, says most investors mistakenly believe they can pick fund managers who can beat the market. Instead, he recommends doing what Harvard does: invest in diversified, low-cost index funds.

🌱 2. Focus on Real Growth: Index funds capture the steady, predictable growth of real businesses, avoiding the risks of speculative stock trading.

When we think of investing, we often picture just stock prices and green-red line charts. If the number goes up, that’s good! If it goes down, we feel sad. It’s easy to forget that when you buy a stock or fund, you’re really buying a piece of a real business, made of people, systems, buildings, etc. This insight can make us approach investing with a much healthier long-term mindset.

Chapter 2 Summary

This chapter breaks down the difference between real business growth and speculative stock trading, showing why it’s smarter to focus on long-term, predictable returns.

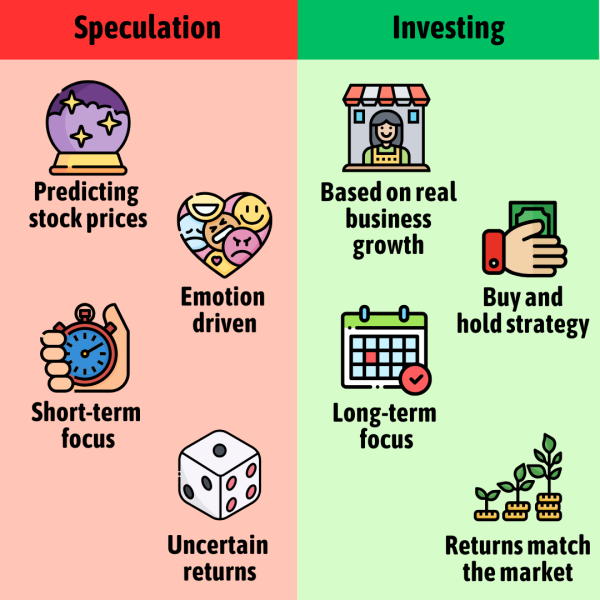

- Investing vs. speculating: The stock market has two parts: real business growth (profits and dividends) and speculative trading (guessing stock prices). Stock prices go up and down daily because of traders’ emotions and predictions. But over decades, 95% of investor returns come from real business growth, not speculation. The takeaway? Focus on the steady growth of businesses because guessing stock price swings has made investors almost no money overall.

- Price/earnings ratio: Real business growth comes from real increases in sales, profits, and innovation. Speculative swings, on the other hand, reflect investor emotions like fear and excitement. These emotions affect the price/earnings ratio—how much investors are willing to pay for $1 of company earnings. During market booms, this ratio can climb too high (like over 30 in the late 1990s), but it always returns to realistic levels over time (typically around 20).

- Regression to the mean: Business returns have been very steady over the past 100 years, averaging 9% annually and rarely turning negative (only during the Great Depression). Speculative returns, however, are unpredictable and swing wildly. After a bad decade, the market usually bounces back strongly—this is called regression to the mean. It shows that speculation is not a reliable way to grow wealth.

Chapter 3 Summary

This chapter shows how index funds capture the growth of real businesses, making them the easiest and most reliable way to grow your money.

- Index funds are the winning strategy: We now know that over time, stock market growth matches the growth of business earnings and dividends. That means, the best strategy is simply to own a piece of all the businesses in the market through index funds. For example, $15,000 invested in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund when it was opened in 1976 would have grown to over $913,000 today. (While this success is impressive, it doesn’t guarantee the same results in the future.)

- Keep it simple: Most complex strategies—like picking the best fund managers or using algorithms—don’t work. In fact, 96% of actively managed mutual funds fail to beat the market after taxes, according to Yale’s David Swensen. A principle called Occam’s razor says the simplest solution is usually the best, and that’s true for investing too.

- Types of stock market indexes:

- 1) The S&P 500 tracks the 500 largest U.S. companies by market size (market cap), representing 85% of the U.S. market. For example, Apple makes up 3.2% of the S&P 500, so it accounts for 3.2% of the index fund.

- 2) Total stock market funds include a wider range of 3,000+ companies and perform nearly the same as the S&P 500, with a 99% match in returns. Both are excellent options for capturing market growth.

In the recent bestselling book The Psychology of Money, author Morgan Housel emphasizes the point that chasing higher than average returns is a fool’s game. Almost everyone who tries to do it ends up making less than the stock market’s average return, while taking on a lot more risk. Paraphrasing Warren Buffett, that book tells us, “There is no reason to risk what you have and need for what you don’t have and don’t need.”

💸 3. The Cost Advantage: Minimizing fees, taxes, and expenses is the most reliable way to maximize your long-term returns.

There’s an old sports cliche that “Offense wins games, but defense wins championships.” When it comes to investing, so many of us focus almost exclusively on offense—how to make it grow faster. But we too often neglect defense—how to avoid others taking our hard-earned money through costs. Yet this second part of the equation can make an even greater difference to our wealth over time.

Chapter 4 Summary

This chapter shows why keeping costs low is crucial for success in the stock market.

- Costs eat your wealth: Actively managed mutual funds charge 2-3% per year through expense ratios, sales charges, and trading fees. These costs directly reduce your returns, which is why most investors underperform the market. While the stock market has averaged 9.5% annual returns over the last 100 years, the average investor only earns 4.5% after subtracting 2% fees and 3% inflation.

- The compounding effect of costs: Just like your returns grow over time, costs also add up. A 2% annual fee may sound small, but over 50 years, it has a huge impact. For example, $10,000 invested at 7% grows to $294,000, but at 5% (after 2% fees), it only grows to $114,000. That missing 60% goes to intermediaries, even though you took all the risks and provided the money.

Chapter 5 Summary

This chapter explains why choosing a low-cost fund is smarter than relying on a fund’s past performance.

- Past performance doesn’t predict the future: Many people pick mutual funds based on past success, but that doesn’t mean they’ll do well in the future. A stronger predictor of higher returns is simply choosing funds with lower costs.

- Beware of survivorship bias: Mutual funds often seem better than they are because about 25% of them disappear over time, usually due to poor performance. This makes the surviving funds look more successful than they actually are.

- The cost advantage: In the author’s analysis, over 25 years, the lowest-cost funds averaged a 9.4% return, compared to 8.3% for the highest-cost funds. This difference is mostly accounted for by the difference in fees between the two. It might seem small, but it adds up: low-cost funds would grow your money 8x over 25 years, while high-cost ones only grow it 6x. Index funds, with fees as low as 0.1%, let you keep almost all of the market’s returns.

Chapter 6 Summary

This chapter explains why dividends are so important for growing your wealth over time, and how low-cost index funds multiply their impact.

- The power of dividends: Dividends are payments that companies give to shareholders, usually as a portion of their profits. They are a steady source of income for investors, accounting for 4.2% of the S&P 500’s annual returns on average. They are also very reliable, dropping only during major crises like the Great Depression and the 2008 financial crash.

- Reinvesting dividends: If you invested $10,000 in the S&P 500 in 1926 and reinvested the dividends, it would grow to nearly $60 million today. Without reinvesting dividends, it would grow to less than $2 million from stock price increases alone.

- Keep costs low to maximize dividends: High mutual fund fees can eat up 60-100% of your dividend income, especially when yields are low. In contrast, index funds with fees as low as 0.1% take only a tiny portion, allowing you to fully benefit from compounding returns of reinvesting dividends over time.

Another great personal finance book—from almost 100 years ago!—is The Richest Man in Babylon. It’s an entertaining read, with money wisdom hidden within short stories set in the desert, with camels and gold.

This book coined the idea of “Pay yourself first,” meaning to first put a part of every paycheck into your own savings, before taking care of other expenses and purchases. When we pay ourselves first and live off what’s left over, then we will grow our savings. When we first pay everyone else, then buy what we want, then there is usually zero left over at the end of every month.

📉 4. Why Most Investors Underperform: Most investors earn less than the market due to emotional decisions, high fees, and taxes.

John Bogle doesn’t have a very high opinion of the investment fund industries as a whole. He (correctly) believes they are primarily driven by the desire to make those selling the funds rich, rather than being in the best interest of the investors. He spends a lot of time underscoring the downsides of an active investing strategy, including ways we might not have thought of before.

Chapter 7 Summary

This chapter explains why most investors earn much less than the market, caused by poor emotional investing decisions.

- The gap between market and investor returns: Over the last 25 years, the S&P 500 returned 9.1% annually, while equity mutual funds returned 7.8%. Yet, the average mutual fund investor only earned 6.3%. After inflation, this gap can cut your potential future wealth by more than half over 25 years.

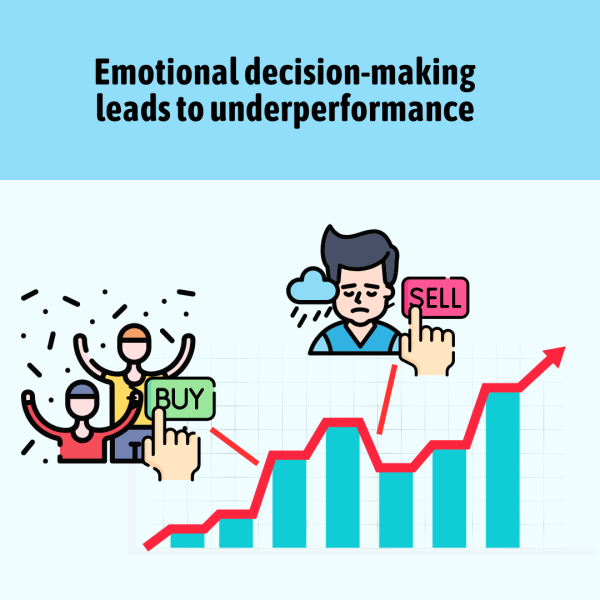

- Why investors underperform: Emotional decisions, driven by fear and greed, lead to bad timing and poor choices. Investors often buy when prices are rising, influenced by market hype or fund marketing—usually right before a drop. Then, they panic and sell when prices fall, missing out on the recovery. During the Dotcom bubble of 2000, for example, investors poured money into high-tech stocks, only to sell after the crash, doubling their losses.

- The solution: Stick to a simple, low-cost index fund and hold it for the long term. This removes emotional decision-making, timing, and stock selection, helping you outperform 85% of other investors who fall into these common traps. Index funds help you avoid reacting to market hype or fear—so you can stay disciplined and let your investments grow over time.

Chapter 8 Summary

This chapter explains how taxes can quietly eat into your investment returns—and how index funds can help you avoid this.

- The cost of taxes: Over time, taxes can take away tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars from your returns. Actively managed mutual funds trade stocks often, holding them for an average of just 19 months. Every trade triggers taxes, adding up to about 1.2% in annual tax costs.

- Why index funds save you money: Index funds trade very rarely and hold stocks “forever,” resulting in much lower tax costs—less than 0.5% annually, mostly from dividends. By minimizing taxes, index funds help you keep more of your returns and are a smarter choice for long-term investing.

Chapter 9 Summary

This chapter explains why future market returns will likely be lower than in the past and why low-cost index funds are the best way to protect your gains.

- Future returns will be lower: Over the past 40 years, the S&P 500 had unusually high returns of 11.7% per year, much higher than the historical average. John Bogle predicts future returns will be much lower—4% for stocks and 3.1% for bonds. Why? Dividend yields are expected to stay low around 2%, P/E ratios will likely drop from 30 to the historical average of 20, and interest rates will return to normal levels after being unusually high in recent decades.

- The future for the typical investor: Based on these predictions, a 60% stocks and 40% bonds portfolio is expected to return only 3.6% annually. After subtracting 2% for inflation, the real return drops to just 1.6%. For those investing in actively managed funds with 1.5% fees, the net return could be as low as 0.1%.

- Index funds will help in slow times: Low-cost index funds, with fees as low as 0.1%, allow you to keep more of your returns. In a low-return environment, this difference is critical—wouldn’t you rather earn 1.5% instead of just 0.1%? In a world of lower returns, avoiding high costs is more important than ever, and index funds are the smartest choice to maximize your gains.

🎲 5. Avoid Chasing “Winners”: Short-term mutual fund success is often due to luck, not skill, and rarely lasts.

Betting on a sports team may feel exciting, make the game more engaging, and provide an emotional payoff—a big hit of dopamine—if they win. In that situation, we are speculating who is going to win, trying to predict the future, which is always a risky move. How can we predict which team will win a game? Perhaps by looking at their past record to see how many games they’ve won in the past year. Many people take that same mindset towards investing, but as you’ll see… it’s not that simple.

Chapter 10 Summary

This chapter explains why it’s nearly impossible to pick mutual funds that consistently beat the market and why index funds are the smarter choice.

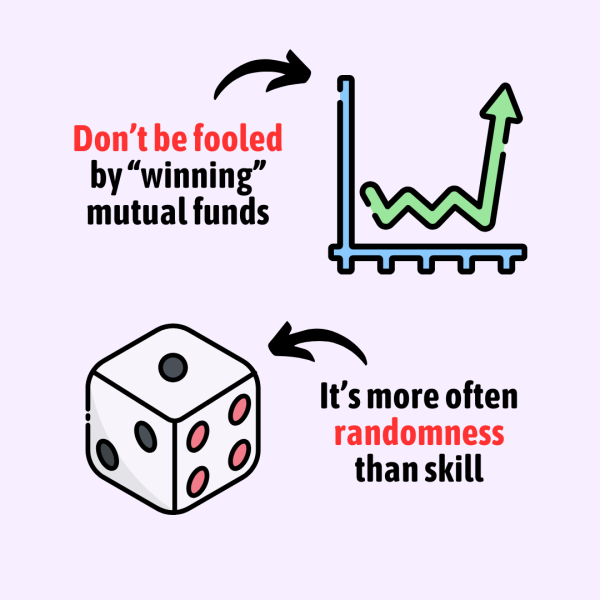

- Don’t try to pick “winning” funds: Your chances of selecting a fund that consistently outperforms an index fund are only about 0.5%. Here’s why: Over 46 years, 355 mutual funds were analyzed. First of all, 80% of them no longer exist—most were closed due to poor performance. Of the remaining funds, almost all were within 1% of the S&P 500, likely due to luck. Only two funds outperformed the market by more than 2%: Fidelity Magellan and Fidelity Contrafund.

- The rise and fall of a “winner”: Even the two “winning” funds have a disappointing story. For example, The Magellan Fund, managed by Peter Lynch, started small with $7 million in assets and outperformed the market by 10% annually during its early years. As its extraordinary success gained attention, billions of dollars poured in, and by 1999, it managed $105 billion. But as the fund grew, its performance declined, falling below the S&P 500 for the next 20 years. That means most investors who joined missed the golden years and ended up with poor returns. By 2016, the fund’s assets had dropped to $16 billion. The lesson? Index funds offer a more reliable way to invest without the risk of trying to pick a fund that beats the odds.

Chapter 11 Summary

This chapter explains why a mutual fund’s short-term success is usually random and doesn’t last.

- Reversion to the mean: Funds that outperform in the short term often return to average—or worse—performance later. This phenomenon, called reversion to the mean, shows that exceptional results are usually just statistical flukes. A few good years don’t guarantee ongoing success; instead, they’re often followed by weaker performance.

- Short-term performance doesn’t predict the future: Many investors rely on Morningstar ratings, especially 4- or 5-star funds, to choose investments. However, these ratings focus heavily on recent performance, with 35% of the score based on the last two years. A Wall Street Journal study found that after 10 years, only 14% of 5-star funds kept their rating, while more than half dropped to 3 stars or fewer.

- Investors are “fooled by randomness”: Top-performing funds often seem like winners because of luck, not skill. Nassim Taleb’s idea of being “fooled by randomness” explains this: If you start with 10,000 fund managers flipping coins to determine winners, by year two you have 5,000 winners, by year three you have 2,500 winners… and by the end of year five you’ll still have 313 “winners” with a perfect 5-year track record—but only due to chance.

Chapter 12 Summary

This chapter explains why financial advisors often fail to choose better-performing funds but can still provide useful financial guidance.

- Financial advisors don’t pick better funds: It might seem logical to trust experts to outperform regular investors, but research proves otherwise. A Harvard Business School study found that funds chosen by professionals earned just 2.9%, compared to 6.6% for funds chosen by individual investors. Yet 70% of people invest through these intermediaries.

- A conflict of interest: Many stock brokers earn commissions by selling certain funds, so they often push trendy but risky investments. For example, Merrill Lynch launched their Internet Strategies Fund during the 2000 dot-com bubble. It was a hit product, selling $1.1 billion, but within two years the investors had lost 80% of their money, and the fund was shut down. An a positive note, there’s a growing trend toward fiduciary duty, which legally requires financial advisors to act in your best interest.

- What financial advisors are good for: While advisors can’t reliably pick winning stocks or funds, they can assist with critical tasks like managing taxes, saving for retirement, and building a portfolio based on your risk level. To get the best advice, look for an advisor who recommends low-cost index funds as part of their strategy.

💵 6. Start Early to Maximize Compounding: The sooner you start investing, the more time your money has to multiply and grow exponentially through the power of compounding.

The Walton family controls 50% of Walmart has seven members who are billionaires. How? From the beginning, Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart, assigned significant shares to his children and wife, saying it’s better to “give away your assets before they appreciate.” While not all of us can have that kind of early advantage, it’s always better to start sooner with investing. As that old proverb goes, “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is today.”

Chapter 13 Summary

This chapter wraps up the case for index funds, highlighting how their low costs and simplicity make them the best choice for long-term investing.

- The power of low costs over time: Researchers used a fancy tool called a Monte Carlo simulation to compare an index fund with a 0.25% fee to a mutual fund with a 2% fee. After one year, 29% of mutual funds outperformed the index fund. But over 50 years, only 2% managed to beat it—matching the real-world data we discussed where just 2 out of 300+ funds have consistently outperformed.

- Not all index funds are the same: Index funds can have very different fees. For example, Vanguard charges no sales fee and has an expense ratio of just 0.04%, while Wells Fargo charges a 5.5% sales fee and a 0.8% expense ratio. If you invested $10,000 in the Wells Fargo index fund and your friend invested the same in the Vanguard fund, 33 years later you would have $63,000 less due to higher fees.

Chapter 14 Summary

This chapter explains why bond index funds are better than actively managed bond funds and why bonds are an important part of a balanced portfolio.

- Why own bonds at all? As you probably know, bonds are loans you give to companies or governments that pay you back with interest over time. Bonds generally have lower returns than stocks—5% annually over the last century and an estimated 3% for the next decade—but they reduce risk. Bonds provide steadier returns and help balance your portfolio, so when stocks drop, you’re less likely to panic and sell at the worst time.

- Bond index funds win with lower fees: Bond index funds outperform actively managed bond funds because they have lower fees, no high sales charges, and are more tax-efficient. According to the SPIVA (S&P Indices vs. Active) report, bond index funds beat 85% of actively managed bond funds over 15 years. The lower expense ratios explain most of this gap.

- Why actively managed bond funds fail: Bond yields (returns) depend mostly on central bank interest rates, so managers can’t do much to outperform. Some take risks by buying lower-quality or junk bonds, but these strategies generally backfire down the road.

A more recent book on index fund investing is The Simple Path to Wealth. When it comes to saving money for investing, here’s a great tip from that one I like: “Stop thinking about what your money can buy. Start thinking about what your money can earn.”

📊 7. The Downsides of ETFs: New index fund options like ETFs and “smart beta” ETFs may sound innovative, but they often encourage risky behaviors or overcomplicate investing.

Over the last few years, we’ve heard a lot about Bitcoin, NTFs, and cryptocurrencies. Before AI took over, it was the hottest tech topic in the world. In finance, there’s always the cool new thing that promises to change the game. Most often, it doesn’t. While the new things talked about in this book are a lot less speculative than Bitcoin, John Bogle cautions us to beware falling for hype and marketing.

Chapter 15 Summary

This chapter explains what ETFs are, how they work, and why traditional index funds may be a better choice for long-term investors.

- What are ETFs? Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) let you buy stock indexes throughout the trading day, like individual stocks. Broad U.S. stock index ETFs, such as the SPDR 500 ETF or Vanguard 500 ETF, can be great when used for long-term investing and are sometimes slightly more tax-efficient than traditional index funds.

- Cautions about ETFs:

- Encourages bad behavior: Real-time trading can tempt investors to trade too often or try to time the market, which usually leads to worse results. For long-term investors using a buy-and-hold strategy, real-time trading isn’t really an advantage.

- Many ETFs focus on speculation: Only 32% of ETFs track broad stock indexes. Most target specific sectors or strategies, turning investing into risky speculation. This goes against the principle of broad diversification and often leads to underperformance.

- ETFs benefit the financial industry, not investors: Financial companies promote ETFs as a trendy product to attract investors who are enticed by chasing unrealistic returns. While ETFs now hold more than half the money in index funds, many investors misuse them.

- Why traditional index funds are better: Traditional index funds avoid the risks of frequent trading and speculation. They better reflect the core benefits of index investing: simplicity, diversification, and long-term reliability.

Chapter 16 Summary

This chapter explains “smart beta” ETFs, a new type of index fund that claims to deliver higher returns but often falls short.

- What are smart beta ETFs? Smart beta ETFs are similar to traditional index funds but weight stocks differently. Instead of using market cap (a company’s total value), they focus on factors like dividends or other financial metrics to try and outperform the market. Marketed as innovative and exciting, smart beta ETFs have quickly grown to $750 billion in assets within 10 years.

- They don’t perform better: Research shows that the first two smart beta ETFs had risk-adjusted returns 97% identical to traditional index funds. At best, they mimic index funds but with higher costs. At worst, they’re a form of active investing in disguise. Their biggest flaw is reversion to the mean—factors that outperformed in the past often don’t continue to do so. In contrast, traditional index funds reliably capture overall market growth without unnecessary complexity or added risk.

Chapter 17 Summary

This chapter explores how Benjamin Graham might view index funds. He was the father of value investing and Warren Buffett’s mentor.

- Who was Benjamin Graham? Graham was a legendary money manager and author of The Intelligent Investor. He pioneered value investing, where you analyze companies to find undervalued stocks. However, later in life, Graham questioned whether this approach was still effective because so much research was already being done. He criticized Wall Street for focusing on earning commissions rather than helping investors succeed, noting that the market as a whole can’t outperform itself.

- He’d likely support index funds today: Graham lived before index funds existed, but his key principles—such as diversification, avoiding high fees, and setting realistic long-term expectations—align closely with index fund strategies. He believed most people, unless investing full-time, should take a defensive approach and aim for steady, reliable returns. Warren Buffett, a close collaborator of his, told John Bogle in 2006 that low-cost index funds are the best choice for most investors and that Graham would have shared this view.

🛠 8. Balance Risk with Bonds: Your mix of stocks and bonds should match your risk tolerance, age, and financial goals.

To a compete beginner, investing feels very risky, like gambling with your hard-earned money. While there is risk, it is manageable. So much of learning how to manage our money is the strategies to reduce risk, like adding more diversification, not trying to guess short term stock prices, and including more stable investments into the mix. This way, we can sleep better at night.

Chapter 18 Summary

This chapter explains how to split your money between stocks and bonds.

- Why allocation matters: Benjamin Graham believed your asset allocation strategy—how much you put into stocks vs. bonds—was the most important choice in investing. A 1986 study found it determines 94% of returns for institutional investors.

- Simple rule of thumb: Start with 50/50 stocks and bonds. Adjust to 75/25 for more growth or 25/75 for more stability. Including bonds reduces your long-term growth slightly, but it also protects your wealth during market downturns—instead of dropping by 40%, your savings may only drop by 20%, which is a lot easier to stomach.

- How to decide your split: The two main factors are:

- Age: Younger investors often go for more growth (stocks), while retirees prioritize stability (bonds).

- Risk tolerance: Can you handle market drops without panicking? Do you have upcoming financial needs like retirement, kid’s college, etc.

Chapter 19 Summary

This chapter explains more strategies for balancing investments, planning for retirement, and managing withdrawals.

- Target Date Funds (TDFs): These funds automatically adjust your stock-to-bond ratio as you approach retirement, making them a simple, hands-off option. They’re now the most popular choice, managing over $1 trillion in assets. Always check that the TDF you choose uses low-cost index funds.

- Popular retirement accounts:

- 401(k) and Traditional IRA: Contributions are tax-deductible, but you’ll pay taxes on withdrawals in retirement.

- Roth IRA: A great choice for many new investors. You contribute after-tax income, but your money grows tax-free, and you won’t pay taxes when withdrawing in retirement.

- Withdrawing 4%: Dividends (2%) and bond interest (3%) alone may not cover your expenses in retirement, so you’ll likely need to sell some shares. A good rule of thumb is that you can withdraw 4% of your portfolio each year. Stay flexible: during downturns, withdraw less than 4% to avoid selling at low prices, and reinvest more during market upswings.

Chapter 20 Summary

This chapter explains why index funds are based on timeless principles, and why it’s smart to start now, even with an uncertain future.

- Certainties amidst uncertainty: While the future is unpredictable, we can be sure of a few things: the long-term risk of not investing outweighs the short-term risk of market ups and downs, investing early lets you benefit from the miracle of compounding, and keeping costs low allows you to maximize returns. While no one can reliably beat the market, index funds guarantee you a fair share of its growth.

- Timeless wisdom from Benjamin Franklin: The principles of index investing align with Benjamin Franklin’s 300-year-old wisdom that continues to resonate, like “He that ventures nothing gains nothing” (you need to invest to grow) and “A small leak will sink a great ship” (control your costs).

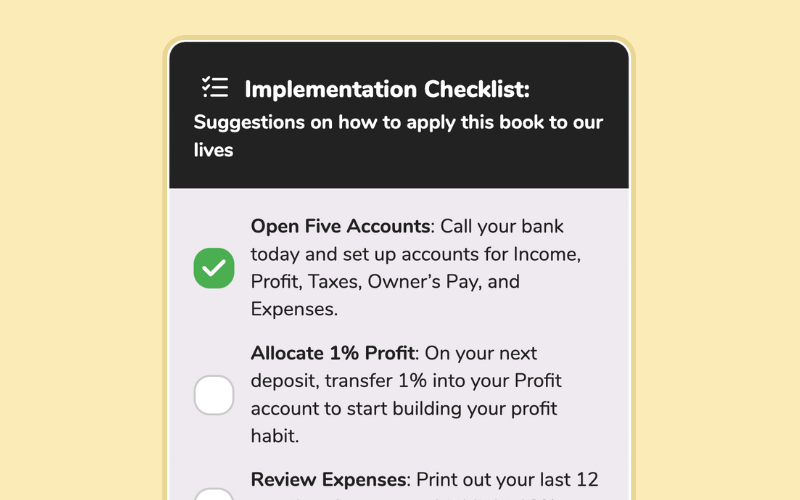

- Buy a low-cost index fund: Open an account and invest in a fund like the Vanguard S&P 500 (VOO) with fees under 0.1%.

- Reinvest your dividends: Enable automatic reinvestment to grow your money faster through compounding.

- Cut costs immediately: Switch to low-fee funds or platforms, and avoid advisors charging more than 1%.

- Set an investing schedule: Check your portfolio only monthly or quarterly to avoid emotional decisions.

- Avoid chasing “winning” funds: Stick to a broad index fund instead of chasing short-term success stories.

- Start investing today: Contribute a set amount monthly, even if small, to build consistent habits.

- Use ETFs wisely: Buy and hold broad ETFs like VTI, and avoid trading or niche sector ETFs.

- Balance risk with bonds: Adjust your stock-to-bond ratio based on age (e.g., 80/20 for young investors).

- Automate contributions: Set up recurring deposits to your investment account so you never miss saving.

- Rebalance yearly: Adjust your portfolio to maintain your target stock-to-bond ratio.

Community Notes