Beeping phones, overflowing inboxes, endless newsfeeds, and clever advertising algorithms that can almost read our minds. It’s no secret our world is becoming noisier every year. We’re bombarded with new technology, but we never received a guide for managing it effectively. This is the guide.

Cal Newport is a computer scientist, but ironically his big message in Deep Work is that it’s good to disconnect. So hide your phone and unplug the wifi, because you’re about to learn how to focus! It’s all about setting aside dedicated blocks of time, free of distraction and interruption, to accomplish “deep work.” If you study the lives of the most accomplished people, you’ll see they all made time for this type of deep concentration, including Bill Gates, JK Rowling and Charles Darwin.

- Part 1 of Deep Work explains why deep work is so important for succeeding in our modern economy. Newport believes learning to focus deeply on challenging tasks is the best way for most people to move ahead in their careers.

- Part 2 shares practical advice on how we can get more deep work done. It’s all about creating daily work rituals, training our concentration and minimizing interruptions.

Who is Cal Newport?

Cal Newport is a Computer Science Professor at Georgetown University. Over the last decade, Newport own career has been fantastically productive. He launched a popular blog, had 7 books published, and wrote many academic papers—that have now been cited over 4000 times!

🌊 1. Shallow vs Deep Work: Learning the difference

Newport learned the crucial importance of focusing deeply while earning his PhD at MIT. There he saw the most accomplished researchers staring at a whiteboard together for many hours at a time, just thinking deeply about some scientific problem. While studying the lives of great people in history, he often saw the same pattern: they made deep concentration a priority.

So the most important idea in the entire book is the difference between shallow work and deep work:

- Shallow Work doesn’t require much concentration or skill, and generally produces little value. For most knowledge workers, this includes constant communication through email, messaging apps and meetings. Generally, a smart college graduate can be trained to do shallow work quickly.

- Deep Work requires sustained focus without distraction, which allows us to develop new skills and produce high-value work that is hard to copy. For knowledge workers, this may include crafting a marketing campaign, coding an app feature or optimizing a business procedure. Generally, deep work requires skills and expertise that must be developed over a long time.

When I was around 18, I spent months studying copywriting, learning how to write sales pages that convince people to buy a product. Then I made an online course and was able to sell it successfully because I had learned copywriting, a skill that is truly valuable and difficult. (And by the way, good copywriting is really 90% market research and empathy, mixed with 10% sales techniques like those explained in the book Influence by Robert Cialdini—our summary here.)

Shallow work is undemanding, repetitive, and doesn’t produce much value. Instead, you should be doing more deep work, which requires sustained concentration on a mentally challenging task. It allows you to build skills and finish more complex work projects.

🎯 2. Aim for Depth: Deep work is valuable, rare and meaningful

In Part 1 of this book, Newport argues deep work is becoming more valuable and more rare, plus it brings meaning to our lives. Let’s explore these three points one-by-one:

- Valuable. Deep work helps us learn complex skills, and use those skills to produce high-value work. In the past, you could be successful doing shallow repetitive work, but those jobs are disappearing because of automation and other reasons. On the other hand, today the internet allows people who are the best at any skill to reach a worldwide audience and earn huge rewards. According to scientist Anders Ericsson, the key to developing world-class skills is deliberate practice, which involves sustained concentration and corrective feedback.

- Rare. Working with sustained concentration is becoming less common today because of popular business trends like constant digital communication and open offices. Cal Newport argues large organizations have a “metric black hole”—they can’t really measure the cost of individual workers being interrupted by a lot of shallow work. And since most workers are not evaluated on deep work time, they instead fall into paths of least resistance: either doing what is easiest now (like emptying their inbox again), or doing what makes them look busy to their boss.

- Meaningful. Doing work that is engaging and challenging can put us into a state of mind called “flow,” first described by psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi. He discovered people feel the most fulfilled when they are deeply engaged in some activity, not when they are relaxing in leisure.

The author Nassim Taleb has some fascinating insights into economics. In his book The Black Swan, he says we are transitioning from an old world to a new one. The world we used to live in is called Mediocristan, where things were more equal and similar. But the world we are moving into is called Extremistan, where individual outliers can be extremely different than the average.

For example, something that exists in the world of Mediocristan is human height—most people are a similar height, around 5-6 feet tall. But something that exists in Extremistan is success—Bill Gates is richer than 1000 other people combined and JK Rowling sells more books than 1000 other authors combined, etc. We are slowly living more in this new world of Extremistan, where it really pays to be the best in your field, but it sucks to be average.

Today, deep work is becoming more rare and valuable because of technology trends like the internet and automation. Doing work that is engaging and challenging feels more meaningful, too.

⏰ 3. Create Daily Rituals: Personal habits make deep work easier

Why do so many of us find it hard to concentrate? Maybe our problems can be explained by two recent ideas from psychology:

- Willpower. Most of us think willpower is like a character trait, but researcher Roy Baumeister has discovered willpower is more like a muscle. Each morning we wake up with a limited amount of willpower that gets depleted over the day as we exert effort, make decisions and resist impulses. The best way to avoid using up our willpower too quickly, according to Cal Newport, is to set up daily work rituals (or habits) that make deep work almost automatic.

- Attention Residue. Switching your focus too often between multiple tasks decreases your performance, according to business Professor Sophie Leroy. It’s almost like some of your attention remains stuck on what you were working on before. This is a problem for many modern workers, who may spend their whole day being interrupted by email, messaging apps and coworkers stopping by. The solution is to plan longs blocks of time to focus on one project without any of those interruptions.

We often imagine geniuses working chaotically and being struck by inspiration at random times. In reality, many of the most accomplished people in history had repetitive daily rituals to help them focus and structure their work life. Many examples Cal Newport shares came from another book literally called Daily Rituals, by journalist Mason Currey who documented the day-to-day work habits of over 100 influential artists and thinkers. He found that no two individual had the same rituals, but they had all created daily rituals to support their creativity—that’s the most important point.

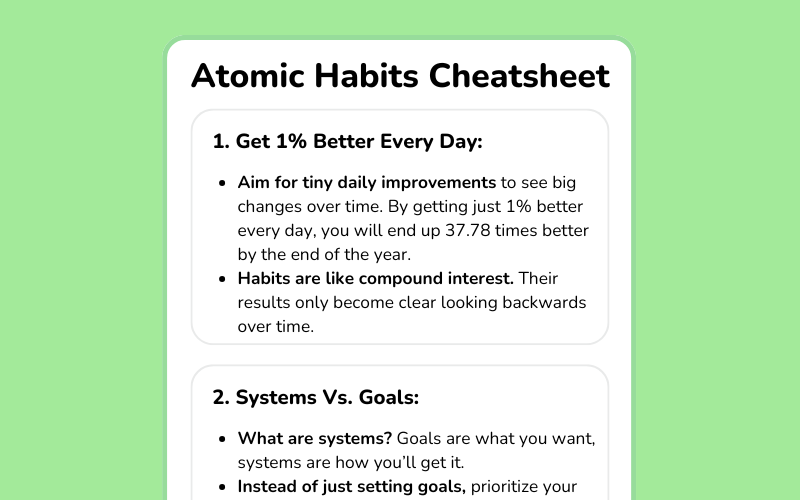

Here is a great analogy that communicates the power of habits, from author James Clear: “Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement. The same way that money multiplies through compound interest, the effects of your habits multiply as you repeat them. They seem to make little difference on any given day and yet the impact they deliver over the months and years can be enormous. It is only when looking back two, five, or perhaps ten years later that the value of good habits and the cost of bad ones becomes strikingly apparent.”

Willpower is not a character trait, but more like a muscle that gets tired out over the day. Create daily rituals so you can avoid depleting your willpower too quickly. These should involve long blocks of time focusing on a single task, so you don’t suffer the effects of attention residue.

🧠 4. Find Your Work-Style: Four common ways of working deeply

Cal Newport has noticed four major styles of deep work:

- Monastic. You become basically unreachable, like a religious monk. This way of working is best for those who work alone on long-term projects, like writers and academics, allowing them to truly dedicate their lives to their craft. For example, science fiction writer Neal Stephenson doesn’t have a public email address, because for him every minute spent on email is one less minute writing his next novel.

- Bimodal. You switch between being unreachable and being connected, for long stretches of time. This is great for those who need to focus deeply, but have other work obligations too. For example, the great psychologist Carl Jung built a secluded house in the countryside where he worked deeply for months every year, but he would always return to the busy city, to work in the Universities and with his patients.

- Rhythmic. You set aside blocks of time to work deeply within your normal schedule. This is good for people with a busy full life, who are still trying to get deep work done. For example, one of Cal Newport’s associates writes academic papers for 2 hours every morning, before he goes to the job that pays the bills.

- Journalistic. You do bursts of deep work whenever you have time to spare. This can be the right option for those who have busy and irregular work schedules. For example, Cal Newport himself is a busy father, so he fits in extra writing time when his kids are taking a nap.

In running my online businesses, I like to spend most of my work days focused on deep work. Then every 2-3 days, I reserve blocks of time for shallow work, like email. This works great for me, but I’m not sure if it’s possible for everyone. One big advantage of being self-employed is that I can set up my work to not require constant email communication with others. This is possible even within a company with many people. For example, in the software company Basecamp, the founders were located in different parts of the world. So when one of them was working, the others were often sleeping. This gave them time to do their most valuable work without distraction.

The four major styles of deep work are: 1) monastic—being basically unreachable, 2) bimodal—switching between long stretches of concentration and connection, 3) rhythmic—daily deep work within a regular schedule, and 4) journalistic—fitting in deep work where possible.

🚫 5. Minimize Interruptions: Remaining concentrated on one task

Here are three tips for being interrupted less often while you are working deeply:

- Schedule your deep work. Plan out your blocks of deep work time, these should include at least: what you’ll be working on, a start time, and an end time. When you’re in one of these blocks, don’t switch to anything else for even a minute! (Remember attention residue we talked about before.) However, Cal Newport is flexible with his time blocks, moving them around as his day unfolds.

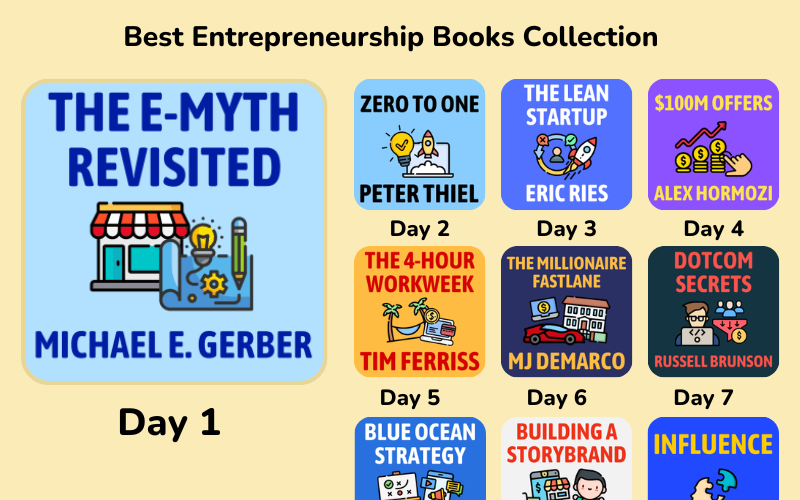

- Check email less often. Most of us assume we must respond to emails quickly, but this is often not true. Consider how you could explain the costs of too much shallow work interruption to your boss, clients or coworkers. In The 4-Hour Workweek (our summary here), author Tim Ferris explains how he began checking his emails twice per day. He let senders know about his email routine with an auto-reply message, which also included his phone number for emergencies.

- Avoid open offices. The idea of open offices was really a misunderstanding, argues Cal Newport. Experts were studying why so much innovation came from certain places, like Bell Labs in the 1950’s, they believed it was because employees from different disciplines could run into each other often. However, they didn’t have big open office plans we see today, but secluded offices mixed with common areas where researchers could mingle.

Remaining focused on one thing while you are working is crucial, which means eliminating interruptions. Schedule blocks of time to do deep work and avoid checking anything else. Newport is critical of companies that promote open offices and constant digital communication.

🧘♂️ 6. Train Your Concentration: Your ability to focus can be increased

Stanford Professor Clifford Nass studied people who multitasked often, and he discovered their brains were actually changed so they couldn’t concentrate as effectively. What if focus is not a fixed ability, like most of us assume, but more like a muscle that we can strengthen?

One of my favourite quotes ever on personal growth comes from Stephen Covey: “The ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person. Reactive people are driven by feelings, by circumstances, by conditions, by their environment. Proactive people are driven by values—carefully thought about, selected and internalized values.”

When we choose to be productive, we are using willpower to strive for our long-term values instead of giving in to our short term impulses. Perhaps this is the most important way humans are different from other animals—we have that power to choose not to follow our instincts.

Read more in our summary of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey

Cal Newport shares some ways we can train our willpower and concentration:

- Pre-schedule internet browsing time. Instead of jumping online whenever you get bored, plan out your internet use beforehand, then resist going online until that time. This can increase your mental willpower, just like the physical resistance of lifting weights at the gym helps people grow stronger.

- Reconsider your use of social media. Most people think it makes sense to use social media if they can find any benefit to it, says Cal Newport, but this is a very unsophisticated way for a worker to choose their tools. Instead, we should weight both the benefits and the costs of each tool, like social media. We must also consider the “opportunity cost” (EconLib.org) of not investing that energy into other activities that are probably more vital to your career.

- End your work at a fixed time. Newport doesn’t work on weekends or past 5-6PM on weekdays, although many professors in his position believe it is essential. He believes this clear “shutdown time” helps his productivity because his subconscious mind works on problems in the background when he’s not working. Also, research shows we can only do deliberate practice for 1-4 hours per day, so any work after that is more likely to be shallow.

By the way, don’t worry if you find it difficult to avoid social media, infotainment sites and shiny apps. That doesn’t mean you’re weak, it just means you’re normal! Giant tech companies spend hundreds of millions of dollars to make their apps more addictive, and many of their methods are explained in the book Hooked by Nir Eyal. I think it’s work reading that book to learn how tech gets us addicted, so then we can avoid their tricks.

For example, one way apps make us return to them again and again is through triggers, which include notifications, emails, etc. So we can backwards-engineer that. If you find yourself being pulled back into a distracting app over and over again, then remove the triggers. Turn off notifications, unsubscribe from emails, etc.

You can strengthen your concentration through resisting impulsive gratification. Plan your internet usage time beforehand, consider both benefits and costs of social media, and set a fixed shutdown time for your work.

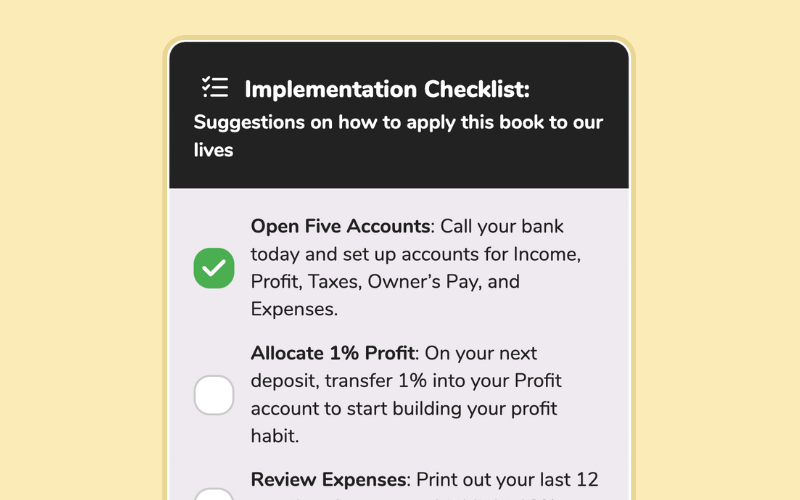

- To reduce your shallow work time, regularly ask yourself: Could a freshly hired person in my company be taught to do this work quickly, or would they need months/years of training? Deep work generally requires developing long-term skills or specialized expertise.

- How can you reduce time spent on email? By setting new expectations with your coworkers, having set times when you will check your inbox, or another way?

- If you use social media, consider not just the benefits of it but also the costs, including the opportunity costs of not spending that energy elsewhere. For example, if someone is a blogger, they may receive some small benefits of exposure by using Twitter, but they would probably receive much larger benefits using that energy to do more research, writing and individual outreach to other bloggers.

Community Notes