Negotiation is the best. It is a core skill we need to be an effective salesperson, manager or leader… and it can even help nations avoid going to war!

The problem is that most of us don’t know how to negotiate. Or if we do negotiate, then we do it badly. Some people may avoid negotiating altogether because old-fashioned bargaining can sound awkward and confrontational.

This book Getting to Yes wants to change all that. The experts at The Harvard Negotiation Project created a new method called Principled Negotiation that allows us to work WITH the other sides to find the best agreement or solution for everyone, rather than fighting AGAINST them as an enemy. They wrote down their method in this book, which became a best-seller and is often required reading for business and law students.

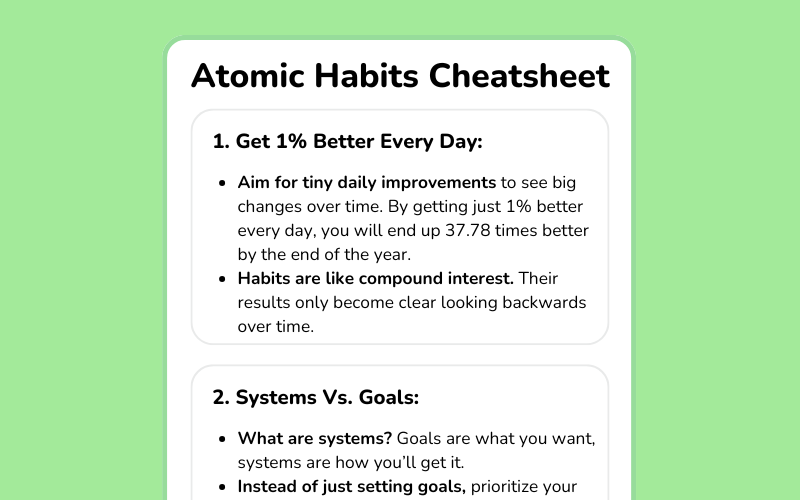

The 4 steps of Getting to Yes are:

- Working side-by-side with the other people to attack the problem together.

- Discovering the real underlying needs and interests of everyone involved.

- Brainstorming creative alternatives or options that meet everyone’s needs better.

- Finding fair, objective outside standards or criteria to help us agree on the final decisions.

Sounds interesting, right? In this book summary of Getting to Yes, we’ll run through some of the most useful lessons and tips found in the book super quick. Let’s go!

About the Authors

Roger Fisher (Wikipedia.org), William Ury (WilliamUry.com), and Bruce Patton (Harvard.edu) were three top experts on negotiation at Harvard University. Beyond their writing and teaching, they have also consulted with large companies and governments to help resolve business conflicts, reach peace agreements in the middle east, and prevent international nuclear war. (That escalated quickly!)

🤝 1. See the People: Principled Negotiation is about working side-by-side to fulfill everyone’s interests

The classic Hollywood scene of negotiation is a tense standoff. It’s like two characters in business suits sitting across from each other at a desk, staring at each other without blinking or smiling. Maybe if the writers are having fun, they’ll also add some shouting and swearing. It’s not a pretty picture!

Even in real life, negotiations can be less than pleasant. Most often, we fall into a tug of war over the price or other factors. For example…

Mike tries to buy a used car and says, “I’ll give you $2,000 in cash for it.”

And the owner Bob says, “No way! It’s worth at least $5,000!”

Mike says, “That’s impossible! The best I can do is $3,000.”

Bob replies, “How about we split the difference at $4,000?”

Then Mike sighs and pulls out his wallet, “Fine, but you’re really giving me a hard time here, Bob.”

The authors of Getting to Yes call this “positional bargaining.” It’s based on choosing a starting position, often without much reason, and then trying to give up less of your position than the other side. Whoever gives up less, “wins.” But nobody really wins because this way of negotiating is slow, inefficient and sometimes destructive to the long-term relationship.

Both sides have an incentive to start with an extreme position. But with each compromise from that position, they may feel like they’re losing. Our pride tends to become involved and we can easily feel disrespected by attacks on our position, like our needs are being ignored.

The self help book that everyone has heard about is How to Win Friends and Influence People. And the most important point in that book is that everyone deeply desires a “feeling of importance.” So to become a great leader and get along with others, we must take care not to damage people’s “feeling of importance” by direct confrontation, overly harsh criticism, expressions of contempt, etc.

Here’s one of my favourite quotes from that book: “When dealing with people, let us remember we are not dealing with creatures of logic. We are dealing with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudices and motivated by pride and vanity.” That is incredibly important to keep in mind as we are negotiating or communicating with anyone!

Learn more in our summary of How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

What’s the solution? That’s our next lesson…

Principled Negotiation starts with a commitment to solve everyone’s problems in the agreement, rather than feeling like we’re working against them. This requires moving past the idea of negotiating between two opposing positions.

👂 2. Listen for Needs: Underneath people’s words and their “position,” you can find their real interests

This next part of Getting to Yes is about finding out: what does everyone really need? What are the true interests that can be solved in this negotiation? And, most of all, how does the other side really see the situation and feel about it?

How? By listening! Listen! Listen! Listen! The authors recommend asking questions like “Why?” and “Why not?” when they say their position or reject your position. (Do this in a tone of voice that is curious, not accusatory!) The goal is to discover their motivations, feelings and needs. This will usually reveal new factors that dramatically change the negotiation, as you’ll later see.

Another top expert on negotiation is Chris Voss, who worked for the FBI for 24 years and became their top hostage negotiator. As you can guess, during those decades he mastered many highly effective negotiation techniques. After all, he was dealing with criminals, kidnappers and terrorists. But in his recent bestselling book, he ALSO emphasized the incredible power of simply listening.

Voss wrote, “It all starts with the universally applicable premise that people want to be understood and accepted. Listening is the cheapest, yet most effective concession we can make to get there.” In any negotiation, he always tries to summarize the other side’s position back to them, in his own words, to demonstrate he is listening and understands their situation.

Learn more in our summary of Never Split the Difference by Chris Voss

In particular, you’ll want to listen for:

- Basic human needs — Like for safety, autonomy, recognition, etc. When you identify the real need that is underneath a position, it becomes possible to meet that need in some other way in the final agreement.

An example I can think of: imagine someone wants to work from home, but their boss says no. They ask questions and find out their boss is worried about their work performance dropping at home. So the employee could offer to work from home, but with some clear goals for their work productivity. - Common interests — Can you find common goals, even outside of the current deal? There may be opportunities to include something new in the agreement to address those common interests.

An example from another book: when the CEO of Disney bought Pixar in 2006, a big reason the deal was signed was that Disney committed to preserving the unique culture at Pixar’s headquarters. Pixar didn’t want to change, and Disney also didn’t want them to change because they were making so many great movies. It was a win-win. - Opposite interests — Can you look for differences that are complementary? In other words, is there anything you value highly the other person does not? Or can you find something that would cost you little to include in the agreement, but provide a lot of benefit to them?

Another example from me: a car dealership may not be able to lower the car price any lower, but if they discover the buyer needs winter tires, they could include those at their discounted wholesale price. The buyer saves money in a different way, while the dealership sells the car at the price they need to. - Their obstacles — Can you find any problems that make the deal difficult for them to execute? Simply making the execution more easy and convenient for them can all make the difference.

I recently finished the biography of Steve Jobs, who was a very intelligent negotiator. When Jobs launched the iTunes Music Store, he needed to sign deals with ALL the major music companies, which was a minor miracle. Jobs accomplished it by making the deals very easy for them. Apple would take care of everything: the music player, software, online downloads, copyright protection, payment processing, etc.

Listen with care to find the real interests and needs of the people involved. These are the driving force beneath their stated positions. Listen for basic needs like for safety, hidden obstacles to execution, and shared interests (or differing interests) that may reveal surprising opportunities for cooperation.

🍰 3. Expand the Pie: Brainstorming alternative agreements that meet everyone’s needs better

When we begin a negotiation, it’s easy for us to get stuck in a kind of tunnel vision. Both sides start with conflicting positions, and we assume the solution must be found in a straight line between those two positions. So we argue about who will get a bigger slice of the pie. But there’s no reason to believe that!

The best agreements are more about expanding the pie, so everyone gets a bigger slice at the same time. Yes, this is possible because we don’t NEED to compromise between positions, instead we CAN invent a creative new agreement that meet everyone’s needs better.

Brainstorming is the best way to begin creating a better agreement. This means proposing many ideas to meet everyone’s interests, without holding back.

During this brainstorming stage, a rule of “no-criticism” is highly recommended by the authors of Getting to Yes. First, get a ton of ideas on paper without judging them. Only later move to a second stage of eliminating the unrealistic ideas and refining the good ideas into something realistic.

I know that many professional writers follow a similar process. Their first stage in writing is a free-flowing rough draft, their second stage is careful editing. Or as one writer said: “write drunk, edit sober.” (But I don’t think anyone will recommend going to your next negotiation drunk!)

One of the most important social psychologists ever is Daniel Kahneman, who won the “Nobel Prize in Economics.” In his brilliant book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman separates people’s decision making into two categories. He says we have one system for making decisions that is quick and intuitive, and a second system that is slow and logical.

It is fascinating that studies suggest using that intuitive part of our mind requires feeling at ease. As Kahneman wrote: “Mood evidently affects the operation of System 1: when we are uncomfortable and unhappy, we lose touch with our intuition.” That may also explain why it is so important to avoid criticism in the first stage of creativity.

Read more in our summary of Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Instead of fighting over a limited pie of two opposing positions, we can expand the pie so everyone gets more. First host a brainstorming session when you invent many creative ideas for ways to meet everyone’s needs better, without criticism. Later refine the best ideas into something realistic.

📏 4. Find Fair Standards: Resolving disputes by pointing to objective measures and pre-existing examples

The fourth and final step of the method is about criteria—this means resolving disagreements in the negotiation with an outside fair standard. It is another technique to avoid that tug-of-war game of positional bargaining. You don’t try to create an agreement based on who can push for their position more strongly, but based on some objective measurement that is generally accepted.

To be specific, objective standards can mean:

- Pre-existing agreements — How have similar situations been resolved before? Pointing towards those precedents can be very compelling. This can also be related to accepted traditions, customs and norms.

- Market data — A lot of information to resolve may be openly available. Like if there is some disagreement about the fair price of a home, both parties can look towards how much similar homes are sold for.

- Expert judgment — If there continues to be disagreement about which standard is the most fair, the best solution may be to decide using a third-party expert, someone both sides agree will make an impartial decision.

I found this part of Getting to Yes very interesting because in some ways it is an “irrational” way to resolve disagreements. I mean that just because people have done something a certain way in the past, that doesn’t mean it’s the right way to do it. But we can’t deny that past precedents are a powerful road when it comes to changing people’s minds or influencing them.

The psychologist Robert Cialdini talks about the principle of social proof. In his words, “[Social proof] states that one means we use to determine what is correct is to find out what other people think is correct.” In other words, we often look towards others to find out what is right, especially in situations when we feel unsure of ourselves. Perhaps this is why the beliefs of most people are a reflection of where they are born, when it comes to which religion is true, what government is best, how to live properly, etc.

To resolve disagreements fairly, don’t compromise between positions, but point towards outside standards. These can include past examples like how similar negotiations were done, or accepted traditions and norms. It could also mean objective market data, or deferring to an impartial expert’s judgment.

💭 5. Gain Leverage With Options: Finding better alternative deals gives you confidence to walk away

Let’s finish up with cool little technique called BATNA, which is short for “Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement.” In other words, you need to know what your best alternatives are, if this deal doesn’t work out. This can mean, for example, going to buy a car already having done good research on prices for similar cars nearby.

There is real power in having options, or at least KNOWING what your next best option is. When you are faced with a deal that doesn’t look great, you’ll know whether you should take it (if your alternatives are bad) or pass on it (if your alternatives are good). In the end, you’ll always have a better result, compared to being blind to your other options.

According to the authors, if your BATNA is great then it can make sense to share it during the negotiation. Like if you are at a job interview and want a higher starting salary, then you will have a lot more leverage if you let the company know you already have other job offers.

Donald Trump, before he became a fiery politician and the US President, was of course a famous businessman. He negotiated some incredibly complex deals, particularly in real estate, like building skyscrapers in New York and a casino in Atlantic City. Trump’s book The Art of the Deal shows that he understood how to use leverage very effectively. And he understood this idea of BATNA, at least intuitively.

For example, one time he was negotiating to buy some waterfront land in New York. First, he talked about the advantages to the buyer of selling the land to him (like that he had the business experience to get the deal approved by the authorities quickly). Next, he took a step back and talked about the seller’s lack of alternatives (like that New York was in a recession that included real estate).

Trump was painting a picture of the buyer’s other alternatives being much worse than selling to him. His book said it clearly, “If you want to buy something, it’s obviously in your best interest to convince the seller that what he’s got isn’t worth very much.”

Read more in our summary of The Art of the Deal by Donald Trump

Determine your BATNA, or best alternative agreement. This gives you confidence to walk away from a bad deal, or lets you know if you should accept a poor deal when your alternatives are worse. If your alternatives are great, then you can let them know because that can give you leverage and power.

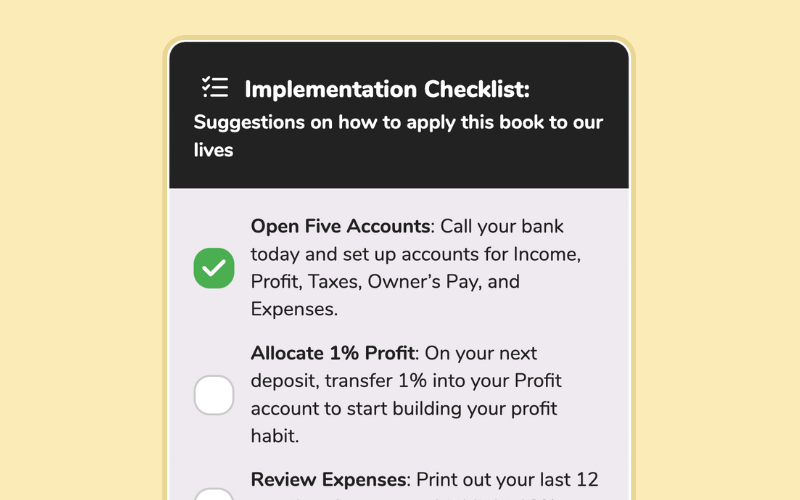

- Write down ONE LIST with everyone’s interests. Instead of getting distracted by everyone’s stated positions, you write down the interests of everyone on one page. This can provide a fresh new perspective to help invent a creative new agreement. This technique is actually called the “one-text procedure” and the authors find it especially useful when many parties are involved.

- Ask “How did you come up with that position?” In other words, you’re asking them to share their reasoning or theory underneath their position, like the price they’re asking for. This is much better than directly saying they’re wrong. Instead you can point towards a more fair standard by which to arrive at an agreement.

- Research your alternative options for 1-10 hours. Obviously the more important the deal, the more time you’ll want to spend here. More than anything else, I think this can help us enter a negotiation with confidence. Doing a little extra research beforehand could give you a lot of leverage in the conversation, information about the current market, and even ideas for creative agreements.

Community Notes