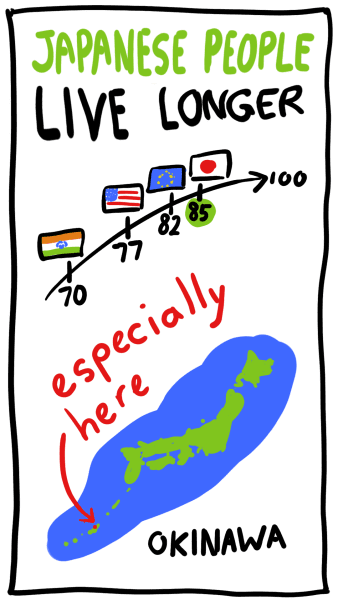

Why do Japanese people live so long?

According to organizations like The World Bank:

- 85 years is how long the average Japanese person can expect to live. That is the highest life expectancy in the world! Japan is also the country with the highest portion of centenarians, which means people living to over 100 years old. That is compared to about…

- 82 years of life expectancy for people in Western European countries, and

- 77 years for the United States.

Do Japanese people have a secret to living longer, healthier, and happier? Some experts believe their secret is not just a healthy lifestyle, but also a Japanese concept called ‘ikigai.’

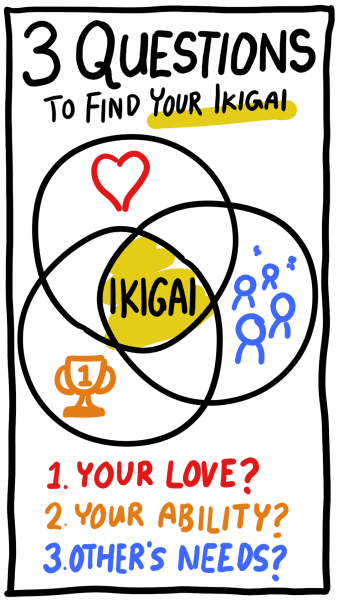

Ikigai means “a reason for being.” It is about having a purpose, a passion, or a powerful reason for getting up in the morning. We are happier and probably live longer when we can do what we love, around people we love.

About the Authors

The idea for this book was born in Tokyo, Japan, where Hector Garcia has lived for over 18 years. The other author is Francesc Miralles, who lives in Barcelona. The book Ikigai was originally written in Spanish and became a surprise bestseller with over 4 million copies sold worldwide.

🌸 1. Find Your Ikigai: Your ‘reason for being’ is found at the intersection of your passion, your ability, and other people’s needs

Sushi, anime, Zen, ramen, Pokémon, bullet trains, and capsule hotels.

What do all these wonderful things have in common? They’re all stereotypes of Japanese culture—they’re what foreigners often associate with Japan, “The Land of the Rising Sun.”

I think that is why this book Ikigai became so popular—because Japanese culture seems endlessly fascinating and different, a mix of ancient and hyper-modern, a place we really could discover “secrets” to health and happiness.

The authors of Ikigai travelled to the place where people seem to live the longest, a small village of 3,000 people called Ogimi on the tropical island of Okinawa in southern Japan.

They interviewed 100 elderly people, most over 90 years old, to find if there was indeed a Japanese secret to living longer.

What did they discover?

Ikigai was a concept that came up again and again. As we’ve already said, it means “a reason for being.”

Most people who lived the longest in Ogimi continued to have very active lives long after ‘retirement.’ They remain busy every day with meeting friends, growing vegetable gardens, drinking tea with neighbours, and celebrating birthdays and festivals.

(For younger people, our career or business will be a large part of our ikigai because that’s what we spend 8+ hours each day doing!)

You can determine your unique ikigai by finding the intersection of:

- What do you love?

- What can you be great at?

- What will the market pay you for?

(This is my simplified version of their 4-part diagram.)

Another major theme in this book is the work of Viktor Frankl, a psychologist who survived the Nazi concentration camps of World War 2. In those camps, millions of Jewish people were killed. But in the middle of all that suffering, Frankl made an astounding observation.

The prisoners who survived found some meaning outside of themselves to look forward to—like a child they needed to take care of or a book they needed to finish writing. But the prisoners who could not find meaning… perished.

After the war was over, Viktor Frankl wrote a book called Man’s Search For Meaning to share the insights that he learned in the concentration camps. Frankl strongly believed mental health and happiness were the result not of becoming passive, but remaining active and contributing to others through family, profession, or community.

Frankl wrote, “What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal, a freely chosen task.” If we don’t find meaning, people resort to poor substitutes, like short-term pleasure and intoxication.

Read more in our summary of Man’s Search For Meaning by Viktor Frankl

The book Ikigai mentions a related psychologist that is more unknown…

Almost 100 years ago in Japan, Dr. Shoma Morita created the Morita school of therapy (MoritaSchool.com) to help people with anxiety. The key idea was teaching patients to accept their uncomfortable emotions, then take action anyway towards their important life purposes. Feel the fear and do what needs to be done. A strong influence on Morita’s work was Zen Buddhism, which is all about accepting life as it is.

You can find ikigai or life purpose by asking: 1. What do you love? 2. What can you be great at? and 3. What will the world pay you for? The psychologist Viktor Frankl survived the WW2 Nazi concentration camps, where he learned the critical importance of finding life meaning. Usually we feel connected to something bigger by serving other people through our relationships or professional calling.

🌊 2. Seek Flow: People are happiest when they’re so engaged in an activity they forget about time

There’s a state of mind called flow. Flow is when we’re so engaged with the activity we are doing that we forget about time. It was first clearly described by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in his book called Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.

I’m sure we’ve all had the experience when we love what we’re doing so much that hours fly by without us noticing. Common activities that put people into “flow” include playing sports, cooking food, painting art, playing a video game, etc.

One of the best ways of finding your ikigai is make a list of which activities put you into a state of flow.

Here are 3 important guidelines for getting into flow:

- It must be challenging. When an activity is too easy, we get bored. When it’s extremely difficult, we struggle. But there’s a ‘sweet spot’ in the middle, where the activity is difficult enough to keep us actively engaged.

- It must have a clear aim. This is why many people feel flow during sports, there’s always a clear target. To score a goal, cross the finish line, etc. However, during the actual activity, our mind is focused on the present moment. It’s a bit of a paradox.

- We must have singular focus. A key element of flow is being fully engaged, which means our mind is totally occupied by what we are doing, rather than thinking about something else. We can improve our ability to focus through certain types of meditation.

Rituals are better than goals for sliding into flow, say the authors of Ikigai. Goals put our mind in the future, while rituals give us an easy way to begin moving into action. (As it happens, rituals are a critical element of Japan’s major religions of Shintoism and Buddhism.) For example, a writer can have a daily ritual of writing down at least 100 words every day, whether he feels like it or not. This ritual will get him closer to finishing a book than obsessing over the end goal.

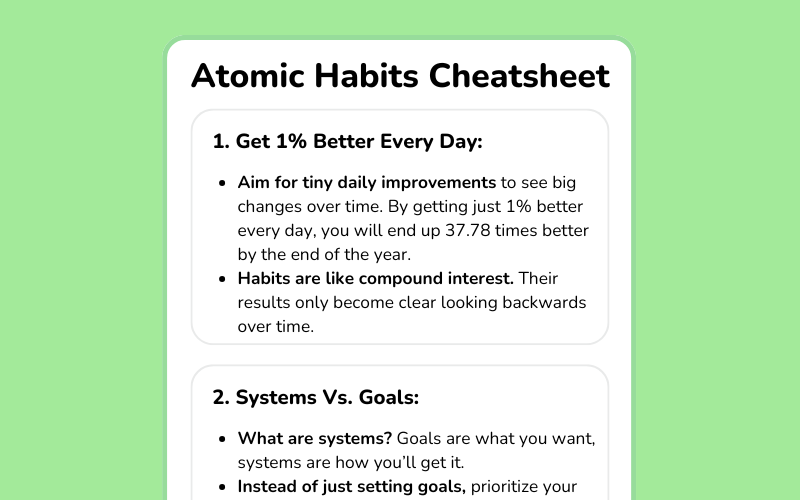

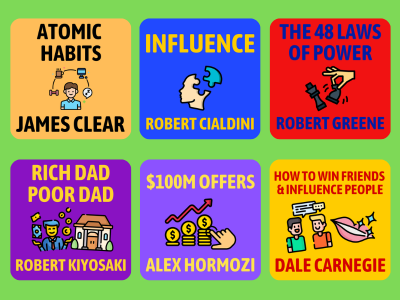

In the book Atomic Habits, the productibity expert James Clear shares a similar idea. To be productive, he says we must forget goals and focus on systems.

Most self-help books would probably say if you want to achieve more, then set more goals. But James Clear says the opposite. He argues that “winners and losers have the same goals.” For example, every athlete at the Olympics has the goal of winning gold, but that alone won’t make them successful. What makes an impact are their daily training and preparation. In other words, their systems.

Systems are the processes we follow to get the results we want. When we focus on systems, then we can become a little better at what we do every day, and that is how people eventually become world-class at anything. The British Cycling team became #1 in the world by focusing on making 1% improvements in every step of their process, which is called the theory of “marginal gains.” For example, one week they would find a slightly more aerodynamic uniform, the next week they would try a better muscle recovery gel, and so on.

… And by the way, that relates back to another fantastic Japanese idea called kaizen, which is about continuous and never-ending improvement. The practice of kaizen is why some Japanese companies like Toyota have such a strong reputation for making reliable high-quality products. They never stop trying to improve every step of their production process.

We all have activities that put us into a state of flow, when hours fly by like minutes. These are a strong hint of what our ikigai is. Remember the activity must be challenging enough, have a clear target, and you must have singular focus. It’s better to focus on our processes and keep improving them daily.

🥗 3. Eat Light: Eating less calories but more nutritious foods (like vegetables) is key to ‘the Okinawa diet’

“Blue zones” are certain small regions in the world where people live much longer than average. The “blue zones” include: Okinawa in Japan, Sardinia in Italy, Loma Linda in the US, Nicoya in Costa Rica, and Ikaria in Greece. The National Geographic journalist Dan Buettner wrote a popular book in 2008 about what people in these regions do differently that allows them to live so long.

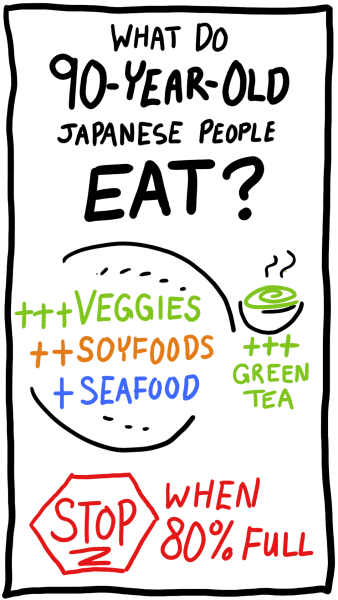

Eating lots of vegetables was one thing all the “blue zones” had in common, which is probably not surprising. In the village of Ogimi, the authors of Ikigai found that EVERY SINGLE elderly person they interviewed maintained a vegetable garden. Researchers say people there eat an average of 7 different vegetables or fruits daily.

Important Okinawan foods include:

- Sweet potatoes are a major staple of the Okinawa diet. A little white rice is eaten daily, though in much lower amounts than mainland Japan.

- Green tea. People there drink 3 cups of ‘sanpin-cha’ daily, which is a mix of green tea and jasmine flowers. Green tea contains many antioxidants which may fight aging, and provides many other benefits for the health of our brain, heart, and immune system.

- Soy foods. Tofu is eaten daily, miso is a fermented paste used to make soup, natto is a sticky breakfast food, and edamame are cooked fresh soybeans.

- Seafood. Fish is eaten 3 servings per week. (That makes sense on a big island!) Seaweed is part of many dishes; it contains many nutrients and vitamins. Pork is eaten 1 serving per week.

Traditionally, Okinawans also AVOIDED eating a lot of: processed foods, alcohol, sugar, and salt. (Today on the island, younger people are eating a more ‘westernized’ diet with more of those foods, so life expectancy is not as exceptional for the next generation.)

Okinawans follow the 80% rule—they stop eating when they are only 80% full. Before a meal, they will often remind themselves by saying “Hara hachi bu” which is basically translated “belly 80% full.” This practice goes back to ancient Confucianism and is also an important part of many religions like Buddhism.

Eating fewer calories in general is probably a major reason Okinawans live so long. They eat an average of 1,900 calories per day, that is hundreds of calories less than the average person in the US. But instead of counting calories, they simply feel when they are getting full, then stop eating.

The best book on anti-aging that I’ve read is Lifespan by David Sinclair, who is a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School. He says that eating fewer calories has been shown scientifically to improve the longevity of many organisms, from humans to mice to yeast. The key is to avoid malnutrition by eating food that is more nutrient dense, like green vegetables instead of white bread.

The easiest way for us to eat fewer calories may be through intermittent fasting, which in practice can be as simple as regularly skipping 1-2 meals. Why is short-term fasting helpful for living longer? Professor Sinclair says it’s because of a biological principle called hormesis, which says that a moderate level of biological stress is actually beneficial to us and activates our ‘longevity genes.’

The island of Okinawa in Japan is one of the ‘blue zones’ where people live much longer than average. The most important dietary factors are probably eating 7+ different vegetables daily and eating less than 1,900 calories per day. Important healthy foods include: sweet potatoes, green tea, tofu and fish.

🎉 4. Relax With Others: Spending quality time with family and friends is almost universal among those who live longest

Stress is not just a bad feeling, it’s actually a biochemical reaction in our bodies. Being stressed floods our bodies with chemicals including adrenalin and glucocorticoids.

What most people don’t know is these chemicals are actually DANGEROUS to our health over the long-term! They increase our risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, and even hurt our immune and reproductive systems.

That’s why it’s so important for us to be able to manage stress. Here’s how…

In all of the “Blue Zones,” people have strong social ties with their family, friends and community. A strong sense of belonging and support is one of the most powerful ways to lower our stress.

Here are some ways the elders in Ogimi, Okinawa nurtured social connections:

- Meeting with friends every day. Almost everyone is part of a small close-knit friend group called a “moai” which provides lifelong companionship and a financial safety net.

- Participating in a neighbourhood association. The town is divided into 17 associations, which give people a place to meet for gatherings, celebrations, festivals, and games.

- Smiling and saying “hello” to people on the street. Perhaps the simplest and quickest way to feel a stronger social connection with our community. (Though I don’t think it would work as well in a big city like New York!)

- Religious rituals, festivals, and services. The main religion in Okinawa is Ryukyu Shinto, which involves worship of one’s ancestors and nature spirits. In general, people in the ‘blue zones’ tend to be involved in a local religious community, and researchers say that helps people live longer.

Most of us have heard the idea that “happiness comes more from relationships than success” since we were small children. However, if you’re interested in self improvement and personal growth, then you probably still have that desire for achievement. And that’s not a bad thing. The key is to make sure we pursue our goals in the correct order…

In the recent bestselling book The Psychology of Money, the author Morgan Housel explains why some people take the desire for material success too far. For example, Bernie Madoff’s name became famous in 2008 after he confessed to running the largest Ponzi scheme in history, defrauding investors of over $64 billion. But why would someone who is already a millionaire do that?

Because our happiness is less about what we get, and more about our expectations. This is just as true for Bernie Madoff, as it is for the ambitious beginner investor or businessperson. As Morgan Housel wrote, “There is no reason to risk what you have and need for what you don’t have and don’t need.” If we can control our expectations for material success, then we can spend more time being happy with loved ones and live longer.

Learn more in The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel (our summary coming soon!)

Strong social connections provide ikigai, lower stress, and help people live longer and happier lives. In Ogimi, elders meet with friends daily, to chat, laugh, drink tea, or play games. In community groups, they celebrate birthdays, festivals, and religious rituals.

🚶 5. Move Mindfully: Continuous gentle exercise is part of their daily routine

Many of us believe a myth that the healthiest people exercise hard. Spending hours in the gym, training for a marathon, perhaps climbing a mountain. But this is a myth.

The people who live the longest stay active and move constantly, but rarely engage in intense exercise. Rather, you’re likely to see them:

- Walking somewhere. To the store, to a friend’s house, to complete an errand. Walking tends to be part of the regular day, not an activity that needs to be planned separately.

- Vegetable gardening. Growing a garden requires daily light work, like digging, watering and weeding. It’s perfect for remaining active with a purpose.

- Movement traditions. Especially in east Asia, several traditional schools have developed that teach practices combining movement with breathing. They include:

- Radio taiso. A series of morning warmup exercises usually done in a group, following an instructor on TV.

- Yoga. A variety of spiritual practices from India. The form of Yoga popular in the West and Japan combines physical poses with breathing.

- Tai chi. An ‘inner martial art’ from China, tai chi involves flowing slow movements of the hands and legs.

The longest-living people tend to engage in continuous active movement, but not hard strenuous exercise. It’s part of their daily routine, such as walking to the store or maintaining a garden. Many practice traditions that combine movement with breathing, like tai chi.

🎨 6. Forget Retirement: Remaining active without an end date is essential to feel engaged with life and others

In Western countries, the great narrative is that we finish school, work a 9-5 job until the age of 65, then we retire to an easy life of leisure.

In Japan, the authors of Ikigai learned a very different way of looking at retirement. Ideally, it doesn’t really exist. More Japanese people in their 70’s are working by choice, often cleaning or looking after others, as a way to keep active and continue giving to society.

If we want our life to keep feeling meaningful, then we must remain engaged with others and our community, by contributing utility or beauty.

The best example to illustrate this mindset are “Takumis,” Japanese master artisans who spend a lifetime obsessively dedicated to their craft. The craft may be anything—porcelain cups, chef knives, or even drawing anime. The books tells a fascinating story about Hayao Miyazaki, founder of the renowned animation company Studio Ghibli. The day after Miyazaki ‘retired,’ he came right back in to the office, sat down at his desk and continued drawing. He just couldn’t stand not doing what he loved most—drawing.

Let’s reflect on this fascinating idea. To most people, the concept of “no retirement” would probably sound strange and awful. Why? Because too many of us hate our work. But how did so many of us get trapped in such an undesirable situation?

There’s an inspiring book called The Alchemist that explains an idea called “Personal Legend.” Your Personal Legend is what you’re always wanted to do, but as we grew older we turned away from it. Instead, we chose a different path because the world convinced us to go for what is practical, respectable, or safe.

As one character in The Alchemist says, “the world’s greatest lie” is that “at a certain point in our lives, we lose control of what’s happening to us, and our lives become controlled by fate. That’s the world’s greatest lie.” At any point, we can choose to start doing again whatever makes us feel excited and enthusiastic.

Remaining active also provides important anti-aging benefits to our brains. Our brain continues to form new connections when it encounters new things daily. That’s why it’s so important to keep learning and putting ourselves into new situations, even those that challenge us or make us feel a little anxiety. (To back up this point, the authors of Ikigai cite Israeli neuroscientist Shlomo Breznitz.)

People in Japan are more likely to keep working part-time even into old age, as a way of giving to society and keeping active, mentally and physically. Contributing utility or beauty to those around us keeps our life feeling meaningful, not endless leisure time.

🍂 7. Embrace Impermanence: To become resilient, we can enjoy each moment, celebrate our flaws, and prepare for the worst

During our lifetime pursuit of happiness and ikigai, it’s inevitable that we will experience setbacks, even tragedy. So the authors include some ideas about how to enjoy life’s beauty and meaning, even if it’s impermanent:

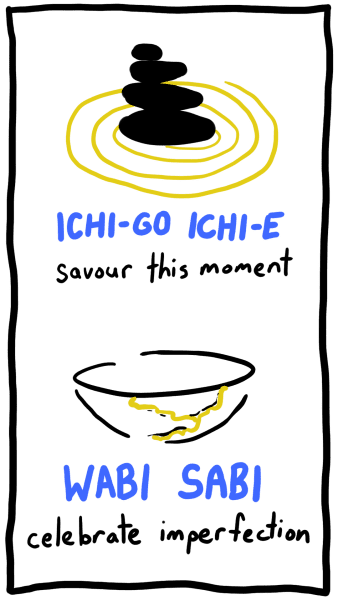

- Ichi-go ichi-e. A Japanese saying that means “this moment will happen only once.” It’s a reminder to enjoy this moment because the same event will never happen again. It’s kind of like the Buddhist saying, “You can never step in the same river twice.” (Because the river is never identical in two different moment. It is always changing, like everything in life.)

- Wabi-sabi. This is another Japanese idea related to seeing the beauty in items that are worn, flawed, or broken. One idea from wabi-sabi is to fix a broken plate with golden glue, so that rather than hiding the flaw we are celebrating it. In the same way, we can be personally proud of many things that are imperfect, unfinished, and impermanent.

- Negative visualization. This is a technique from the Stoic philosophers. They would often prepare for life’s problems by imagining things going very wrong. For example, Seneca would live like a homeless person, to help him become less anxious about losing all he had. (Also read our summary of Letters from a Stoic by Seneca.)

- Antifragile. This idea comes from Nassim Taleb, an economic and financial thinker. Antifragile means that when we are tested, we become better and stronger. It’s a different meaning than resilient, which just says we can withstand tests. The authors of Ikigai say we can become more antifragile by diversifying our sources of income, our relationships, etc.

The authors of Ikigai later wrote “The Book of Ichigo Ichie” and another one called “Wabi-Sabi.” They obviously believe these ideas are important!

The Buddha said “life is suffering” which is often mistaken for being pessimism. The Buddha was simply stating a fact of our lives, that nothing is ultimately satisfying. Everything is impermanent, including all the short times we feel good, content, pleasure, or happiness. Buddha’s solution was a method of meditation. By noticing how everything always changes, we can stop clinging to things, and achieve greater inner freedom.

Learn more in The Heart of The Buddha’s Teachings by Thich Nhat Hanh

Some tools for handling life’s obstacles… Ichi-go ichi-e teaches us to enjoy each moment because it will only happen once. Wabi-sabi is celebrating the flawed, imperfect, and broken. Negative visualization is a Stoic technique, imagining the worst that could happen.

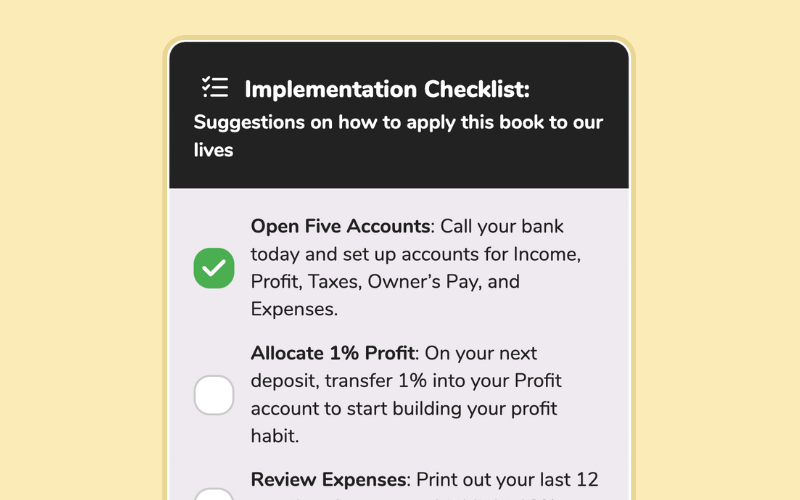

- Make a list of 5 activities that put you into flow. For many people, these are activities that are somewhat challenging and directed towards some goal. Like sports, painting, public speaking, etc. These will be a strong hint of your most important ikigai.

- Make a list of 10 of your potential ikigai. Do this by answering the questions: 1. What do you love? 2. What can you be great at? and 3. What will the world pay you for? Your ikigai will be found at the intersection of these three.

- Write down and imagine the worst outcome of pursuing your ikigai. Often fear stops us from pursuing what is meaningful. We can borrow the Stoic technique of visualizing vividly what it would be like for us to lose our possessions, reputation, relationships, etc. While this sounds terrible, the result is usually that we feel less afraid, after we have defined the worst possible outcome.

Community Notes