Here’s a fair warning. This book is about horrific events that happened in the concentration camps of World War II. If you can’t bear to hear the details, then stop reading here.

But in my opinion, almost everybody should read Man’s Search for Meaning in their lifetime. By reading this book, you’ll gain:

- Deep insights into human psychology.

- Understanding of human evil and history.

- Direction in finding your own life meaning.

Viktor Frankl (Wiki) was a successful professor and therapist in Germany, then his world was turned inside out. Along with millions of other Jewish people, Frankl was sent to the concentration camps built by the Nazi political party, led by Adolf Hitler.

The camps were filled with starvation, torture, suffering, and death. Despite that, Viktor Frankl witnessed some men were able to survive the wretched conditions, by finding meaning. As a psychologist, he helped prevent many deaths and suicides by helping fellow prisoners find meaning. But others who could not find meaning, perished in those camps.

This book was written after the war was over. Viktor Frankl wrote it to help regular people find meaning in their lives. Man’s Search for Meaning became a bestseller in many languages, which Frankl saw as a sad reflection of the reality that modern people are starving for meaning.

🧍 1. True Identity: Discovering your core identity when everything else is stripped away

Viktor Frankl knew the Nazis were imprisoning Jewish people like him, so he got a visa to America. But then he changed his mind. He decided to stay in Austria to look after his elderly parents.

(Indeed, a couple years later Frankl would be at his father’s side when he was dying in one of the concentration camps. He managed to get some morphine to ease his father’s pain during his last days.)

Because of his decision, Frankl was captured and sent to a concentration camp on a train packed with people. Getting off the train, the men and women were separated in different directions.

A Nazi officer examined each new prisoner one-by-one and pointed them to go left or right. He was judging which prisoners looked fit enough to work. About 90% of people were sent to the left line. Frankl was sent to the right line.

What he didn’t know then was that everyone in the left line would be sent to the gas chambers and dead within a few hours.

Viktor Frankl and the surviving prisoners were told to take off their clothes and everything else. Some asked if they could keep a valuable like a wedding ring and they were told no. Frankl begged and pleaded with a guard to let him keep a draft of a psychology book he was writing. It was his life’s work.

The new prisoners didn’t yet understand that everything they had would be taken away.

Then they were shaved. Not just their head but their whole body from head to toe. They were sent to the showers.

With everything gone, a surprising thing happened. A grim sense of humour took over the prisoners. They began making fun of themselves and each other. Frankl would later say that humour is one of the soul’s best defences because it allows you to distance yourself from the devastating reality, at least for a moment.

After the showers, the prisoners stood outside shivering. Standing there naked in the chilly Autumn air, all they had left was their naked human existence. With no clothes, possessions, social position or family tying them to their past, who were they now? Even their names would be abandoned by the officers who gave them each a number.

(By the way, you might want to also read my summary of the book Propaganda by Edward Bernays. It’s all about how perceptions can be manipulated and you will understand how propaganda caused Jewish people to be demonized. When we understand why it happened before, we can stop it happening in the future.)

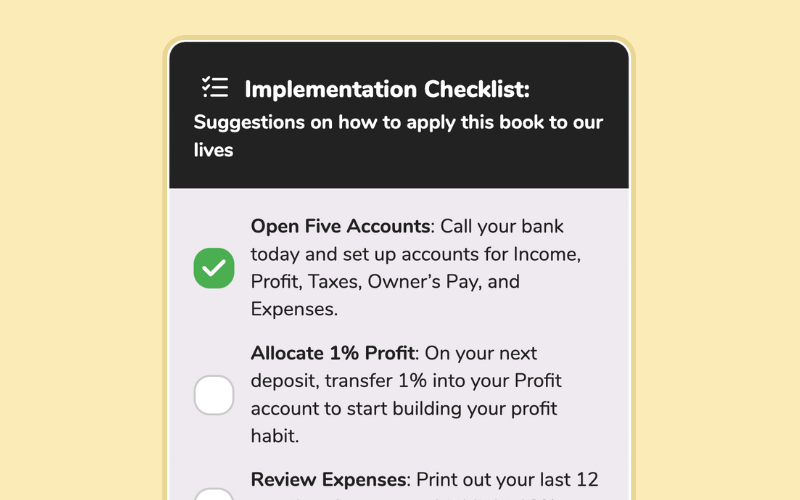

Forced work begins

The prisoners were given thin rags to wear and shoes that didn’t fit. They began working many hours each day. Usually they worked outside, digging the frozen ground to build roads and water pipes. And considering the hard labour, they were not given nearly enough food. Each prisoner received 10.5 ounces (300g) of bread and 1.75 pints (800ml) of thin soup each day, although it was often much less. All of them soon became very thin like skin and bones.

Punishments were harsh and given for the smallest reason or even no reason at all. The guards carried sticks and guns to beat them with. If one of the prisoners stopped digging the frozen ground for even a moment, they would be hit hard. If a prisoner was cleaning the toilets and some of the sewage he was carrying in a bucket splashed into his face, if he even tried to wipe it off he would be beaten.

The guards often made them march for hours over the snow-covered fields. Snow and ice filled their shoes, causing frostbite and itchy, painful swellings. Every step soon became a torture.

Sometimes a tired prisoner would fall down and those marching behind him would stumble and fall on top. The guards then rushed over to beat them all hard with the butts of their guns. Frankl soon learned to march in front of the line so he wouldn’t trip over other prisoners. This helped, yet the marching itself was still very painful. Like most of the prisoners, Frankl was suffering from Edema. This is a condition where his legs and feet became so swollen that his knees could hardly bend and his shoes had to be left untied for his feet to fit.

“If someone now asked of us the truth of Dostoevski’s statement that flatly defines man as a being who can get used to anything, we would reply, “Yes, a man can get used to anything, but do not ask us how.“”

Yet despite all the pain, beatings and suffering, the only way to continue surviving was to look fit for work. If a prisoner had even a small blister on their foot and they were limping a little and an SS guard saw this, they would be sent to the gas chambers. In the first week, an experienced prisoner advised Frankl to shave every day if possible, even if he had to use a broken piece of glass to do it. Shaving would make him look younger and the redness from the scraping might be mistaken for health. It was important for survival.

Everything was taken away from those sent to the concentration camps. Their families, social position, clothes, even their hair. Then their existence was filled with pain through near-starvation, hard labour and constant beatings. Not to mention the threat of the gas chambers hanging over them at every moment.

🌟 2. Hope and Survival: The presence of hope determined survival in the harshest conditions, like those prison camps

At first the new prisoners (including Frankl) were shocked by the brutality of life inside the camp. They couldn’t bear to look when another prisoner was being viciously beaten. But after some time these reactions were dulled. Prisoners who had lived in the camps longer than a few weeks had seen so many beatings, so much suffering and death that they no longer had any reaction. All the prisoners developed a kind of apathy. Not because they were heartless, but as a mental self defence.

Apathy provided an emotional barrier against the daily horrors of the camp and allowed the prisoners to focus all their energy and efforts on the most important task: surviving and helping their friends survive.

Frankl remembers seeing a 12 year old boy come into the sick bay where he was working. The boy had been forced to stand outside in the snow for hours as a punishment and his toes had turned into black, frostbitten stumps. The head doctor couldn’t do anything but pick them off one-by-one with tweezers. Seeing this, the other prisoners in the sick bay could not even be moved to feel disgust or pity because they were already surrounded with so much suffering, dying and death every day.

On top of this, the prisoners had no idea how long they might live in the camps. It might be 2 weeks or 25 years. They didn’t know if they would be sent to the gas chambers tomorrow or if they would spend the rest of their lives here. This situation caused an inner decay in the prisoners because they couldn’t aim at any long-term goal or live with much hope for the future. Frankl said it is a similar feeling of hopelessness that many long-time unemployed workers feel.

(By the way, if you want to learn exactly how feeling hopeless and powerless leads people to join mass movements like Nazism, then look at my summary of The True Believer by Eric Hoffer. Also written shortly after WW2, it provides keen insights into how people can be motivated to do unspeakable things by tapping into their frustration, hate and desire for change.)

Suicide, giving up and illness

Surprisingly, not many of the prisoners attempted suicide. Well, what’s the point of committing suicide if you have such a small chance of surviving until next month anyway? But when someone did attempt suicide there was a strict rule that nobody could try to stop them, like they couldn’t cut the rope of someone who was hanging themselves. This made it very important to stop suicide attempts from happening in the first place.

Some prisoners caught a disease Frankl called “Give-up-itis.” This means they simply gave up one day. Gave up faith in their strength to survive. One morning they would continue lying in bed and not be able to get up no matter how hard the guards beat them. They would continue lying there all day and night in their own excrement.

Frankl said there was always a clear sign that predicted with 100% accuracy that one of these men would be dead within a couple days. What was that sign? The prisoner lying in bed would slowly reach into the folds of their clothes and pull out a cigarette. (In the camps cigarettes were used like money and could be traded for more soup or warmer clothes.) Yet when a man had lost hope, he would light up their cigarettes instead of saving them because they wanted to “enjoy” their last days. This made Frankl realize that when life loses meaning, humans resort to short-term pleasure seeking.

A loss of hope could kill a prisoner in indirect ways too. For example, before Christmas in 1944, many of the men were hoping they would be home in time to spend the holidays with their families. This image kept them going through the cold and suffering. When Christmas came and went, there was a sudden wave of deaths. The head doctor said the deaths couldn’t be explained by any change in food or weather. Frankl believed that losing hope caused a blow to the prisoners immune systems that often proved deadly. When their inner strength or will to live was weakened, latent illnesses or infections could overpower them easily.

The daily horrors of the camp made the prisoners develop an emotional shell of apathy. In spite of that, having hope in the camps was a matter of life and death because it provided inner strength to withstand suicide, illness and giving up.

❤️ 3. Sources of Meaning: Meaning can be found in purposeful work, love, and the way we endure suffering.

Sigmund Freud, often called the father of psychology, said that people are like machines that move towards pleasure and away from pain. That’s why he connected almost anything people did to sexual drives. Another influential psychologist called Alfred Adler disagreed and said that people move towards power. He often echoed Nietzsche’s words that humans have a “will to power” and are always “striving for superiority.”

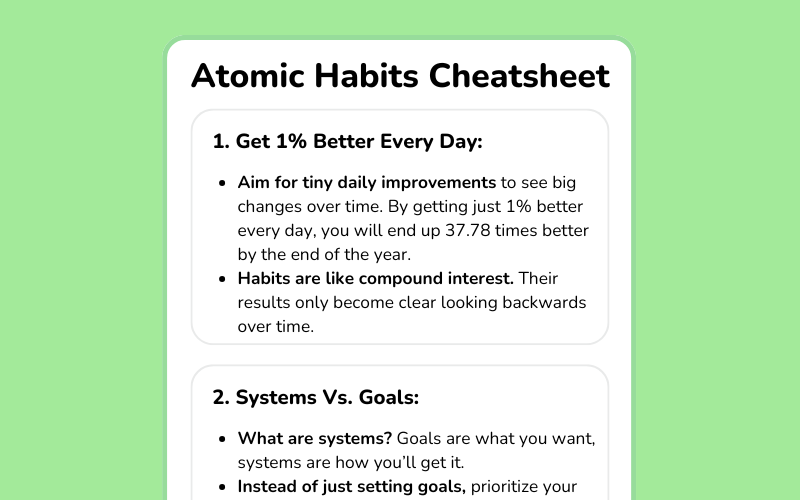

Viktor Frankl admitted that people do want pleasure and power, but we are ultimately driven by a need for meaning in our lives. As he witnessed in the concentration camps, it is meaning that keeps someone alive when all pleasure and power have been taken away. Being a psychotherapist, Frankl tried to help a prisoner re-connect with meaning whenever he could. And he said meaning can be found in any life situation, even a concentration camp.

Now you may be thinking: so what is the meaning of life? Well, asking the question like that is like asking the world’s best chess player “what’s the best chess move?” There isn’t one. There is only the best move at this moment in this situation. In the same way, life meaning is not some abstract definition that will apply to everyone, rather it is about fulfilling the specific meaning in each of our individual lives in this moment.

When Viktor Frankl was younger, he spent 4 years working in Austria’s largest state hospital, in charge of the department where severely depressed patients were treated. Most of his patients were admitted after a suicide attempt. In those four years, he talked to around 12,000 patients, earning a huge stockpile of experience helping the hopeless and depressed.

He discovered there are 3 main ways most of us find meaning in our individual lives:

- Through work (doing or creating something significant),

- Through love (relating and caring for others) or

- Through facing suffering with courage when it’s unavoidable.

What responsibility do you still carry?

Frankl shares the stories of two camp prisoners who changed their minds about committing suicide. Like most suicidal people, both men said they had nothing to look forward to. Now Frankl had learned in his work at the hospital that when someone begins feeling hopeless, the first way to restore their inner strength is to point their attention to some future responsibility they still carry or a future goal they can look forward to.

Talking with the first man, Frankl found after some digging that there was a child waiting for him in a foreign country. The man loved his child very much. He was able to see that nobody else could take his unique place as father to the child, therefore he must survive the daily torture of the camps. Not for himself, but for his child.

The second man was a scientist and after some questioning, he also saw a future responsibility he had to fulfill. Not to a person, but his work. He had written a series of books about his scientific research, but they were still unfinished. The man realized nobody could finish the books but him, so he knew he must survive to finish them.

Suicide was averted when the men could see a responsibility they still carried for someone or something outside of themselves. Many people think you’ll find the meaning of life though sitting on a mountain, inner introspection and a sudden bolt of insight. This isn’t true. Meaning is found in our small daily actions related to something or someone outside of ourselves. Frankl says the more you can forget yourself and dedicate your life to something outside of yourself, the more human you are and this is the “self-transcendence” that gives life meaning.

He also said it’s not our job to ask “what is the meaning of life?” but that life itself is asking us this question at every moment. Every moment it is challenging us to carry out a specific task, assignment, mission or vocation that’s in front of us. It is US who must respond to life’s question—not with talking and thinking—but with our attitude, conduct and actions.

“Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual.”

Meaning in life comes from fulfilling work, loving relationships and courageous suffering. Finding meaning is realizing there is some responsibility you must fulfill in the future, something only you can do. Meaning is usually not found through introspection, but by relating in some way to the outside world.

🔍 4. Meaning in Suffering: Exploring how it is possible to find a deeper meaning within experiences of suffering

Most of us can probably see that meaning is found in relationships or creative work, but what about suffering? Can you really find meaning inside of terrible experiences, especially when they seem to happen for no reason? What meaning can be found in being diagnosed with cancer, being injured by a drunk driver or being thrown into a concentration camp by a lunatic political party?

That’s exactly how many of the camp prisoners felt. If they didn’t survive to escape the camps, then all this pain they were suffering was worthless and it would all be for nothing.

Viktor Frankl saw the situation differently. He knew their suffering would not appear to have value in terms of the normal standards of material success of the outside world. Yet he also believed that if his life’s meaning depended on the random chance they might be set free, then it wasn’t meaningful at all. So he was sure that meaning must also be found in the middle of the worst suffering if it could be found anywhere at all.

“If there is meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete.”

Living inside a camp of suffering and dying men, Frankl saw the only doorway out. He saw that destiny had chosen him to be in this unique place and nobody could suffer in his place now. Thousands of years ago Buddha was right when he said “life is suffering.” If you live, you will suffer. In these situations, the last freedom we have is in how we bear the burden. And we all have those who look down on us from above—God, friends or family, alive or dead—and they would want to see us suffering with dignity, upright and proud. Not cowering from the fate that destiny has chosen us for.

One time Frankl had a doctor come to his office mourning his wife. The doctor couldn’t see anything meaningful or positive about his wife dying, who he’d loved very much. Frankl asked the man what would’ve happened if he had died first instead of his wife. The man thought for a moment and said his wife would have suffered terribly and he wouldn’t want that. So Frankl told the man that he’d spared his wife that suffering, at the price that he would now have to mourn her. The man just shook Frankl’s hand and left. He was better. Frankl knew that suffering somehow stops being suffering the moment we see a meaning in it.

Suffering is an inescapable part of life. You do not need to be suffering now to find meaning in life. However, if your destiny is to suffer, then you can always find meaning in how you respond to your suffering. When your suffering finds a meaning, it is transformed and stops being suffering.

🌟 5. The Last Freedom: Our ultimate freedom lies in our ability to choose our attitude and response in any situation

Do we really have freedom? Some psychologists see humans as merely biological machines, a bundle of instincts and conditioned patterns. Sigmund Freud said that if you took people from diverse backgrounds and exposed them all to severe hunger, then their individual differences would blur. Rich, poor, musician or coal miner… they would all being acting the same way based on one strong urge. Yet Freud’s patients (who he drew his observations from) were all wealthy Victorians laying down on a plush couch in his office.

In the concentration camps where extreme hunger was a reality, it became very clear that how people acted was the result of an inner decision and not just outside influences. Some men became like saints, walking through huts comforting those in pain and giving away their last morsel of bread. Men such as these showed Frankl that a man has an inner strength that may prevail even in the worst circumstances.

Other men made a different choice. They chose to treat their fellow prisoners badly even though they were all suffering. This was especially low. At least when the guards were cruel, it was expected. Yet a few of the guards also rose above the influence of the camp and acted kindly to the prisoners.

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s way.”

When the war was over

Over years, the prisoners became used to the brutality of camp life and the stress of sudden death hanging over their heads. When the war was over, they suddenly felt a large release of mental pressure. This was not totally a good thing. If you ever learn how to dive in the sea, one of the first things they’ll teach you is not to come up too fast from underwater. If you do, the change in pressure can injure you. So you must come up slowly. Well, the prisoners in the camps were also under a kind of pressure and it was suddenly lifted.

Sudden freedom had some unexpected effects on the prisoners:

- At first many of them experienced “depersonalization.” That’s what psychologists call when you feel like nothing is real around you. Maybe they couldn’t believe they were actually free.

- Another surprising effect was that none of them felt much happiness or satisfaction. Although they had been dreaming about freedom for years, they truly didn’t feel as happy as they thought they should. Maybe their emotional system was so adapted to pain and sadness that they needed some time to re-learn how to feel happy.

- Long exposure to the violence of the camp also temporarily warped some of the prisoner’s characters. On the day of Nazi surrender, one of Frankl’s friends rolled up his shirt sleeves and shouted that his hand will be stained with Nazi blood the day he got home. Frankl was shocked because this was not a bad or violent man. Another prisoner didn’t think there was anything wrong with walking right through farmer’s fields, trampling their crops. He said it was perfectly justified considering what they had just gone through and he was deeply offended when Frankl said they should walk beside the fields.

“Only slowly could these men be guided back to the commonplace truth that no one has the right to do wrong, not even if wrong has been done to them.”

Even when the former prisoners came home, the suffering was not over. What can you say to a man who has survived years in the camps for the sake of his family and when he comes home he finds nobody survived? Or how do you stop someone from becoming bitter when all the neighbours can say is they didn’t know about the camps and that they have also suffered? Viktor Frankl found out at the end of the war that his wife was dead. In these times, more than ever, they were confronted with the freedom to choose their inner response. Otherwise a deep disappointment and bitterness threatened to bend their character.

Some of the prisoners in the concentration camps were selfless and kind, others were selfish and mean. This was also true of the guards. This showed Frankl that we always have the freedom to choose our response to whatever life brings us. That is one thing nobody can take away from you.

💖 6. Meaning as Therapy: Finding meaning can serve to nurture and heal our soul—our mental well-being

When Viktor Frankl came home after the war, he dove deeply back into his work and research. He knew that many of the insights he gained about mental health inside the camps could also help modern people.

In his therapy patients, Frankl saw boredom becoming a leading cause of suffering for modern people. Boredom was now bringing as many people into therapist’s offices as the conventional psychological diseases. Boredom really means you don’t have meaning in your life. There’s nothing you live for and care deeply about, so life becomes boring.

In the past, people had traditions that brought meaning to their lives. These traditions gave them direction and certainty. They believed wholeheartedly that if they followed a prescribed way of living and specific rules, then they would be a good person and go to heaven. With many of the old traditions losing credibility among young people in developed countries, many of them struggle to feel connected to something bigger than themselves.

What’s worse is that we have more leisure time than ever before. Why is that bad? Because at least when you’re engaged in something you feel like you have a goal and purpose. When our ancestors hunting a mammoth or foraging for food daily, they were engaged with life and felt alive. In modern times, Frankl says a crisis in meaning is especially clear among retirees. And as people win more leisure time with advances in automation, it will become an ever-bigger problem.

The beginning of meaning-based therapy

In Frankl’s time, psychoanalysis was the most common type of therapy. This focused on introspection and digging into a patient’s past. People might spend years talking about their childhood and it was their psychoanalyst’s job to “unmask” the root of their problem, which usually involved “unconscious drives” or “defence mechanisms” that were created by childhood experiences.

Although Frankl was trained in psychoanalysis, he thought it was neglecting to help people fulfill their deepest need, a need to find meaning in their life. From his experiences in the concentration camps, he knew that meaning keeps people alive even when all pleasure and power are taken away.

So he created a new school of therapy called Logotherapy which focused not on a patient’s past, but on their future. It was designed to help people find a meaning they were called to fulfill in the future.

Suffering: mental disorder or existential crisis?

Mental suffering is not always a psychological disorder or disease that must be cured. Seeing it this way may cause therapists to go the wrong route, smothering bad feelings under a load of tranquilizing drugs. Rather, suffering is often caused by existential frustration, a concern about whether one’s life has meaning as one is now living it. In these situations, the therapists job should be to guide the patient towards a potential meaning they can fulfill. For a meaning to feel satisfying and significant to someone, they have to feel it is unique and specific to them.

A man who was an important American Diplomat came to see Frankl. For years this diplomat had felt unhappy with his work and he found it difficult to follow American foreign policy. He had spent 5 years with a psychoanalyst who told him his dissatisfaction with his work ultimately came down to his bad relationship with his father. Why? Because the US government was nothing but another father image. So he was advised to fix his relationship with his father and the problem would be solved. After years of analysis he was starting to accept his therapist’s interpretations of reality.

Yet after a few interviews with the man, Frankl saw the real problem was that the man’s need for meaning was not being fulfilled by this job. He deeply wanted to do some other kind of work. Since there was no reason not to quit, the man switched to a new occupation on Frankl’s recommendation and remained satisfied there for years.

Positive inner tension

Some psychologists in Frankl’s time also believed that the key to happiness was getting rid of all inner conflicts and tension. They thought this would bring someone to a relaxed inner state of mental equilibrium. Yet Frankl knew this was a dangerous belief because having no inner tension is not the recipe to mental well being, but boredom. Some positive inner tension is essential to a meaningful life.

“What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal, a freely chosen task.”

Like we said before, meaning is usually based on a responsibility you must fulfill in the future. And whenever you have this kind of a meaning or a goal, there is always a gap between where you are today and where you want to be. To close that gap, you’ll struggle and feel inner tension and pressure. You won’t always feel great along the journey. But in the end it’s a positive struggle, the kind that kills the modern disease of boredom and makes life worth living.

For example, you want to write a book, but you are not disciplined or skilled enough to do it yet. So to write the book, you’ll struggle to close that gap. It’s the same with anything. You want to be a great father or mother, but your temper is too short. You want to be the bodybuilding champion of the world, but you’re just a scrawny kid from a small Austrian village. (I’m talking about Arnold Schwarzenegger here, definitely check out my summary of his autobiography “Total Recall.” So many personal growth gems in there.)

Later in life he would always tell his students not to aim at success directly, because then it would elude them. Rather you should aim for a cause greater than yourself and success will come as a byproduct. It’s just like happiness. People who try too hard to be happy always miss because happiness comes as a byproduct of doing something else.

Older forms of therapy like psychoanalysis were centred on talking about your past. Frankl thought this neglected the deepest human need for meaning. So he created Logotherapy, which helps people find meaning by pointing them towards the future, towards some goal or responsibility they must fulfill. This creates a positive tension as people strive to fulfill a meaning that is unique and specific to them.

Conclusion

It was probably difficult reading about the brutal experiences in the camps. Yet I think it’s that part of the book that makes the practical advice credible. Viktor Frankl suffered in the concentration camps for years, an existence far worse than most of us can even imagine. So when he talks about it being possible to find meaning in any life situation, we can believe him.

If you liked this book, I recommend you also look at the lessons I picked up from Arnold Schwarzenegger’s autobiography. I know it might seem unrelated, but Arnold is someone who really embodies living with enthusiasm and fulfilling the goals you find meaningful.