🚀 1. The Power of OKRs: OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) provide a simple yet powerful system to set clear goals, track progress, and inspire teams to achieve more.

Chapter 1 Summary

This chapter explains how John Doerr introduced OKRs to Google, transforming the company’s growth and focus.

- What are OKRs?: OKRs stands for “objectives and key results.” It’s a simple system for setting ambitious goals (objectives) and measuring success (key results). OKRs break big goals into measurable steps. For example, a school principal’s objective might be to “raise student achievement levels this year,” with key results like increasing test scores by 10%, achieving 95% teacher satisfaction with new tools, and implementing weekly tutoring for struggling students.

- OKRs, a Proven Management Tool: John Doerr learned OKRs from Andy Grove, the legendary Intel leader who turned the company into a global powerhouse. Later, as chair of Kleiner Perkins, a top Silicon Valley venture firm, Doerr has introduced OKRs to countless technology companies. It has now been used successfully by businesses as varied as Disney, Spotify, and LinkedIn.

- The Google Story: When Doerr met Google’s founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the startup had only 30 employees. The founders were extremely ambitious and confident. They believed they could grow as large as Microsoft. But a major problem was they lacked management experience. As a gift, Doerr presented the idea of OKRs to the early Google team, who were gathered in typical startup fashion on beanbags. This system became Google’s way of focusing and aligning the company on their most important goals, and it helped Google achieve repeated 10x growth and billions of users. Today, CEO Sundar Pichai continues to set company-wide OKRs, while thousands of Google employees set personal OKRs to stay aligned.

Chapter 2 Summary

This chapter explains that OKRs came from Intel’s Andy Grove and how John Doerr grew to love the system for productivity and management.

- Learning About OKRs at Intel: During a summer internship at Intel in the 1970s, John Doerr attended a course taught by Andy Grove, Intel’s legendary leader. Grove explained that Intel succeeded because it focused on results, unlike his previous company, Fairchild, which valued knowledge without execution. He introduced the new hires to OKRs as a way to ensure every goal was clear and measurable.

- Where the OKRs Idea Evolved From: Goal-setting in management has been around for a long time. A century ago, Winslow and Ford developed a strict, top-down system where managers set goals and measured worker productivity. Peter Drucker later adapted this for knowledge workers with “management by objectives” (MBOs), giving employees more say in their goals. Andy Grove built on these ideas to create OKRs, focusing on measurable output and avoiding the trap of doing busy work without real results.

- How the Author Learned to Love OKRs: Doerr’s first OKR at Intel was to prove their chip was faster than competitors’ by writing benchmark tests. He quickly saw how OKRs brought focus to his days and made it easier to say no to distractions, even requests from colleagues. At Intel, he saw OKRs coordinate the work of tens of thousands of employees in making microprocessors, an intensely competitive industry that requires precision down to the millionth of a meter. This system helped Intel dominate the industry and solidified Andy Grove’s legacy as one of the greatest leaders in tech, even being named Time Magazine’s Man of the Year for his role in the development of microchips.

Chapter 3 Summary

This chapter explains how OKRs helped Intel defeat Motorola, their biggest competitor, and reclaim dominance in the microprocessor market.

- A Crisis at Intel: In 1979, Intel’s 8086 chip was losing ground to a Motorola chip that was easier to program. While the 8086 wasn’t very profitable on its own, it was critical for getting companies to adopt Intel’s full ecosystem of chips and software. When sales manager Don Buckout sent a warning letter to Andy Grove, it triggered a company-wide effort to fix the problem.

- Launching Operation Crush: Andy Grove launched Operation Crush to make Intel the leader in microprocessors again. The strategy focused on reframing the narrative in sales and marketing. Instead of focusing on ease of use, Intel shifted the conversation to their strengths: a more comprehensive ecosystem and long-term reliability. They convinced CEOs that choosing Intel was the best decision for the next 10 years, not just what was easiest right now. This approach crushed Motorola’s momentum and secured Intel’s market dominance.

- How OKRs Drove Rapid Results: OKRs helped Intel move quickly and align the entire organization, from leadership to individual employees. Within weeks, a plan was in place, and everyone understood the clear goal: “crush Motorola.” OKRs allowed teams the freedom to figure out how to meet the objective while staying focused on results. This clarity and flexibility gave Intel the agility to outpace Motorola and win the battle.

One of the most inspirational biographies for entrepreneurs and business leaders comes from Phil Knight, founder of Nike. Phil always believed in not micromanaging his employees, even as the clothing brand was growing by tens of millions of dollars per year. He often quoted US General George S. Patton, who said, “Don’t tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and let them surprise you with the results.”

For example, when Nike needed to open a new store, Phil would assign the responsibility to an employee without giving them too many directions or limits. He believed that allowing people to direct themselves in how to accomplish things would better unlock their creativity.

🎯 2. OKRs Bring Focused Cooperation: OKRs align everyone on the same priorities, channeling efforts and linking teams to work together with purpose and clarity.

Chapter 4 Summary

This chapter explains how to set OKRs that help you and your team focus on what matters most.

- Begin with asking “What’s most important in 90 days?”: Start by identifying the most important goal for the next 90 days. Quarterly goals are ideal because clear deadlines create urgency and focus. The key question in management is: What activities will have the biggest impact for the effort invested? For example, at Google, increasing the number of YouTube visitors who logged in became a company-wide OKR because it had the highest potential impact on user engagement.

- Focus on 3-5 Key Results: Keep your OKRs simple and focused. Limiting each objective to 3-5 key results ensures you avoid spreading yourself too thin. Steve Jobs summed it up best: “Innovation is saying no to 1,000 things.” And don’t stress about getting your OKRs perfect right away—you can adjust them as you learn and progress.

- Balance Result Metrics with Quality Metrics: Focusing too much on one metric can cause problems. For example, Ford prioritized making a cheap compact car but ignored safety, leading to the Pinto disaster. Hundreds of people died because of the sloppy placement of the fuel tank. To prevent this, balance quantity metrics with quality metrics. For instance, an app developer might pair a goal of increasing downloads to 1 million users with maintaining a 4.5 star user rating, ensuring success doesn’t come at the cost of quality.

Chapter 5 Summary

This chapter explains how the education app Remind used OKRs to focus their efforts, growing from a small idea into a thriving startup with millions of users.

- Where the Idea Started: Remind was inspired by Brett Kopf’s struggles with ADHD and dyslexia. A teacher changed his life by helping him clarify daily priorities and communicating with his mother. Later, at Michigan State, Brett struggled again to keep track of assignments and tests, so he and his brother David built a basic app to send text reminders. While the app helped Brett graduate, it failed in the market because they didn’t talk to their target users: teachers.

- Getting a Chance to Try Again: The startup idea was accepted into Imagine K12, an education startup accelerator. This time, Brett set a key result: talk to 200 teachers in 10 weeks, using Twitter to reach them. Their feedback helped him design a simple concept—a sketch of an app where teachers could safely communicate with students. Teachers loved the idea, giving the brothers the validation they needed to move forward.

- OKRs and Managing Explosive Growth: As Remind’s growth exploded, John Doerr taught the team to use OKRs. They posted their OKRs publicly for all employees to see, helping the company stay focused and aligned. Guided by OKRs, Remind grew from 14 to 60 employees in two years and reached up to 300,000 downloads per day. Investor Chamath Palihapitiya also encouraged them to focus on key metrics, like active teacher usage, instead of vanity metrics like downloads, ensuring sustainable, meaningful growth.

Chapter 6 Summary

This chapter explains how Nuna, a healthcare data startup, transformed its growth by fully committing to OKRs.

- How Nuna Began: Nuna was founded by Jini Kim, inspired by her personal struggles with the healthcare system. Her brother has severe autism, and because her parents didn’t speak much English, Kim had to handle his Medicaid enrollment. This frustrating experience made her passionate about improving healthcare data access. Nuna started as a side project to simplify access to healthcare data but struggled to gain traction in its first two years.

- The Breakthrough Healthcare.gov Contract: To figure out what clients wanted, Kim started attending conferences and talking directly to benefits directors. This helped Nuna sign a few Fortune 500 companies. The big breakthrough came when Nuna won a contract to rebuild the Medicaid database for Healthcare.gov, a massive project managing data for 75 million people. This success grew the company from 15 to 75 employees almost overnight.

- How Truly Committing to OKRs Made the Difference: Kim learned about OKRs at Google but didn’t apply them at Nuna right away. The company’s first attempt at OKRs in 2015 failed because they didn’t fully commit. The next year, they tried again, and this time Kim led by example. She made all her OKRs public, asked for feedback, and made sure all other leaders set their own OKRs consistently. The accountability and focus of OKRs helped Nuna structure its rapid growth and stay aligned as a team.

The Lean Startup by Eric Ries is a must-read for startup founders and product managers. It highlights the difference between vanity metrics and actionable metrics. Vanity metrics can look impressive but don’t show what really matters. For example, a million dollars in sales means little if you’re not making a profit. Actionable metrics, on the other hand, help you understand how users engage with your product and where to improve.

At Eric Ries’ startup, IMVU, they gained millions of users, but their key actionable metric—converting free users to paid ones—was stuck at 1%. Ries split users into groups based on engagement (like how many times someone had used the app) and focused on improvements to move each group forward. This was the key step that helped IMVU grow to tens of millions in revenue.

🌐 3. Transparency Creates Alignment: Making everyone’s OKRs publicly visible fosters accountability, collaboration, and a shared sense of purpose across an organization.

Chapter 7 Summary

This chapter shows how OKRs can align your company, while still giving your people and teams freedom and flexibility.

- The Problem with Old Top-Down Management: In traditional management, goals were handed down from the top and kept private. While this created alignment, it lacked flexibility and discouraged individual contributions. Without transparency or autonomy, employees felt disconnected from the company’s bigger goals and less motivated to perform their best.

- OKRs Provide Transparency and Autonomy: OKRs fix these problems by mixing top-down alignment with transparency and autonomy. Transparency is crucial—when everyone’s OKRs are visible, it builds accountability, encourages collaboration, and keeps people focused on shared goals.

- Empowering Employees Through OKRs: A great practice is allowing employees to choose up to 50% of their own OKRs. This gives them ownership of their work, leading to more engagement and creativity. It also taps into insights from front-line employees, who often have the best understanding of the market. For example, Google’s “20% time” policy let employees work on personal projects, leading to major innovations like Gmail.

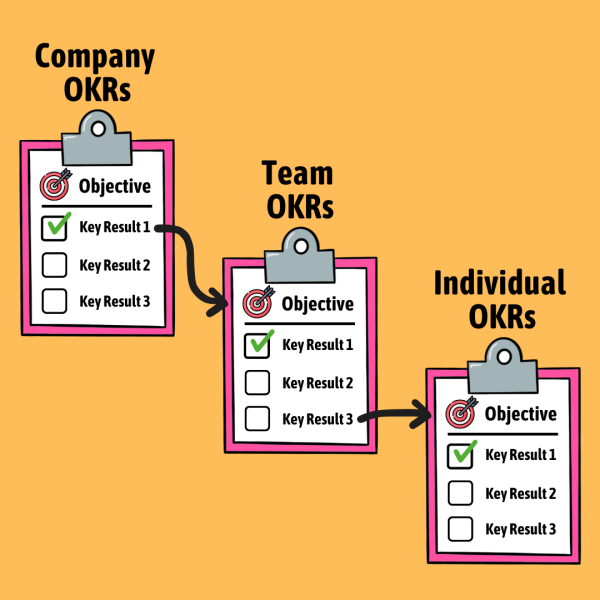

- Top-down alignment happens through “cascading” OKRs. For example, the company starts with one main objective and 5 key results. Each key result then becomes the objective for a major department, and this process continues down to individual employees. This way, everyone’s goals are connected to the company’s overall mission.

Chapter 8 Summary

This chapter shows how MyFitnessPal used OKRs to align their growing team and manage rapid growth effectively.

- How MyFitnessPal Started: MyFitnessPal began as a simple app when founder Mike Lee and his wife wanted to lose weight before their wedding. It tracked exercise and calories. It was easy to manage the project when it was just Mike and his brother Robert running the company. But as the app’s popularity exploded to 35 million users and the team grew, keeping everyone aligned became much harder.

- The Crisis of Growth and How OKRs Solved It: As the team expanded from 10 to 30 employees, productivity didn’t scale as expected. Training new engineers took time, and multiple product managers made conflicting demands on the same team. Critical goals, like sending personalized marketing emails, were missed because of poor coordination. When Kleiner Perkins invested in the company, John Doerr introduced OKRs to provide better structure to the business. The executive team began holding quarterly meetings to set clear, transparent OKRs. This improved efficiency, reduced confusion, and helped align every department toward the same goals.

- From Startup to $500M Sale: MyFitnessPal grew successfully and eventually sold to Under Armour for nearly $500M. Now the founder Mike Lee manages a team of 400+ people and still uses OKRs to keep everyone aligned to common objectives.

Chapter 9 Summary

This chapter explains how Intuit used OKRs to connect its employees and improve collaboration across the company.

- Intuit’s Challenge to Create Connection: Intuit is best known for its software products, including TurboTax, QuickBooks, and Mailchimp. As Intuit grew and shifted from desktop to cloud-based technology while expanding globally, keeping employees connected became a challenge. With teams spread across four countries, including India, it was hard for employees to see how their work fit into the bigger picture. Atticus Tysen, Intuit’s Chief Information Officer, introduced OKRs to help the IT department align their efforts. OKRs allowed employees to see exactly how their OKRs contributed to their manager’s OKRs, their department’s OKRs, and the company’s overall OKRs. This transparency gave employees a sense of purpose and connection to the company’s mission.

- OKRs Enable Cross-Department Collaboration: OKRs didn’t just help within departments—they also made it easier for teams to work together across the company. For example, engineering teams in e-commerce and billing could coordinate directly by viewing each other’s OKRs, instead of relying on their managers to connect them. This transparency turned Intuit from a siloed organization into a collaborative network, improving efficiency and communication company-wide.

🔄 4. Adjust OKRs Based on Feedback: Continuously tracking OKRs provides quick feedback and helps teams adjust direction when things aren’t working, so they keep goals on track.

Chapter 10 Summary

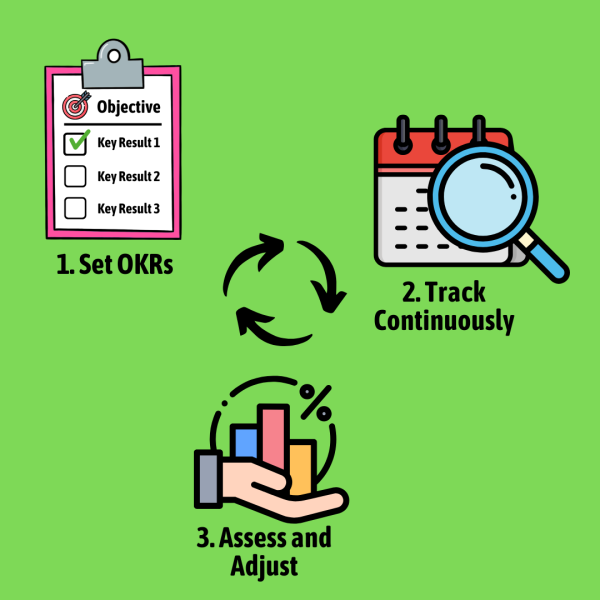

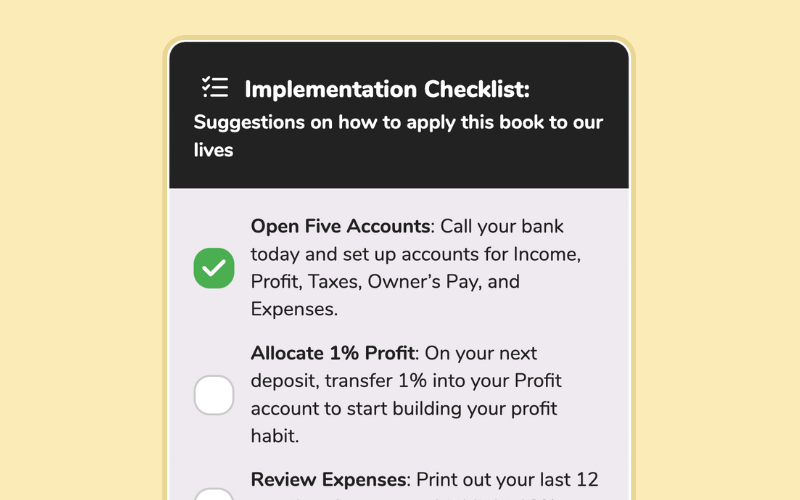

This chapter explains how to track OKRs effectively in three stages: setup, tracking, and assessment.

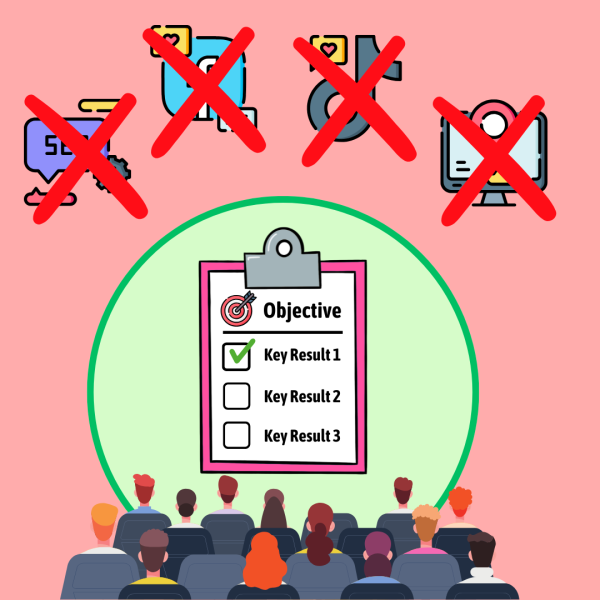

- Setting Up Your OKRs: Organize OKRs in a way that’s transparent and easy for everyone to access. OKR management software works best because it simplifies updates and makes progress visible across the company. Avoid ineffective systems, like one Fortune 500 company that stored OKRs in scattered Word documents for thousands of employees—making it nearly impossible to maintain transparency, as no one is likely to open countless files. To ensure OKRs are set up on time, it’s a good idea to assign an “OKR shepherd” to remind leaders. At Google, Jonathan Rosenberg did this by emailing project managers who missed their OKR deadlines.

- Tracking Them Continuously: Check your OKRs weekly to make sure you’re working on the right priorities. Research by Dan Pink shows that making progress on goals is one of the biggest motivators. If a key result becomes irrelevant due to new information, don’t be afraid to update or drop it mid-quarter to stay focused.

- Assessing for Accountability: At the end of the quarter, evaluate how much of each OKR was completed, usually scored from 0% to 100%. A 70% completion rate is often a success because stretch goals are meant to challenge you. Achieving 100% can mean the goals weren’t ambitious enough. Use self-assessment to judge whether your effort or external factors affected the outcome. Reflect on what worked, what didn’t, and how you can set better OKRs next time.

Chapter 11 Summary

This chapter explains how the Gates Foundation uses OKRs to track progress and achieve its mission to improve global health and reduce poverty.

- The Gates Foundation: Bill Gates founded the Gates Foundation with $20 billion in assets while still serving as Microsoft Chairman. Tackling massive global challenges required a way to track progress, so CEO Patty Stonesifer introduced OKRs. Gates understood the importance of ambitious, measurable goals from his time at Microsoft, where the vision was “a computer on every desk and in every home.” Nonprofits are often great at defining big missions but need clear, actionable objectives to ensure progress—OKRs bridge this gap.

- OKRs Brought Quantified Impact: The foundation used a metric called Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) to measure the effectiveness of their initiatives, which led to a focus on vaccines. Every grant included OKRs with a red-yellow-green scoring system, and grants were rejected if their goals weren’t specific or measurable. This system allowed the foundation to track real progress. For example, they reduced Guinea worm disease cases from 75,000 in 2000 to fewer than 20 per year, making it close to being eradicated like smallpox.

🧠 5. Committed vs Stretch OKRs: Use committed OKRs for predictable, measurable outcomes and stretch OKRs to encourage bold innovation and experimentation.

Chapter 12 Summary

This chapter explains how stretch goals inspire people to achieve more than they would with safer, easier goals.

- Why Stretch Goals Inspire: Stretch goals challenge people to go beyond their limits, often achieving more than they thought possible. Research by Edwin Locke shows that difficult goals increase both performance and engagement, even if they aren’t always reached. For example, Intel’s Operation Crush set a stretch goal of 2,000 design wins—three times the previous record—and that was for a struggling product. They achieved it, partly due to a creative incentive: a trip to Tahiti for any sales person who met their quota, with the added pressure that one person’s failure would disqualify their entire district.

- Two Types of OKRs:

- Committed OKRs are goals you’re expected to meet, usually tied to measurable business outcomes like revenue or customer growth.

- Stretch OKRs are ambitious goals with a high chance of failure (30% or more), designed to inspire bold thinking. For example, some of Google’s moonshot goals, like offering Gmail with 10x more storage than competitors, transformed the entire category. While many stretch goals fail, like Google Answers or Google Circles, they encourage innovation and big ideas.

Chapter 13 Summary

This chapter shows how Google’s Chrome team used ambitious stretch goals to achieve remarkable growth.

- The Birth of Google Chrome: Google’s current CEO, Sundar Pichai, joined the company in 2004 as a product manager working to grow the Google Toolbar’s user base. Using ambitious OKRs, he helped increase users 10x. His next challenge was leading the creation of a new web browser: Google Chrome.

- How Stretch Goals Drove Growth: From the start, the Chrome team set seemingly impossible stretch goals. In their first year, they aimed for 20 million active users but missed the mark. The second year, they set a goal of 50 million users but reached 38 million. By the third year, with Larry Page encouraging them to aim higher, they set a stretch goal of 111 million users and finally hit it by the fourth quarter. These goals pushed the team to avoid complacency, constantly rethink their approach, and try bold new strategies like television ads. A subgoal to make JavaScript run 10x faster seemed unrealistic but succeeded thanks to superstar programmer Lars Bak. Without these ambitious goals, the team might never have achieved such breakthroughs.

Chapter 14 Summary

This chapter shows how YouTube used ambitious OKRs to hit their Big Hairy Audacious Goal (BHAG) of 1 billion daily watch hours.

- Google Bought YouTube: Susan Wojcicki, one of Google’s early leaders, pushed for Google to buy YouTube in 2006 for $1.6 billion. YouTube was already far ahead of Google’s own video platform, making it a smart and strategic acquisition.

- Making Watch Time the Key Metric: YouTube shifted its focus to “watch time” as the main metric for success. Unlike Google Search, where users want fast answers, YouTube’s goal was to keep people on the platform longer. For example, spending 2 minutes on a 10-minute video was more valuable than watching a full 1-minute clip. This focus led to a clear objective: grow daily watch hours from 100 million to 1 billion.

- Achieving 1 Billion Daily Hours: With watch time as their guiding metric, YouTube aligned their efforts and measured every change against its impact on watch time. In the final push to reach their goal, engineers made 150 small optimizations, each improving watch time by just 0.2%. These tiny adjustments added up, helping YouTube achieve their ambitious goal of 1 billion daily watch hours.

Elon Musk, the world’s richest person, is known for setting stretch goals that seem impossible. Early in his career, his startup X (later part of PayPal) aimed to be the first “online bank.” While it fell short, it became the leading online payments platform for years. Later, Musk took on the challenge of creating Tesla, the first successful electric car company, even after major automakers had abandoned the idea.

However, his most ambitious project is SpaceX, with the stated goal of building a human settlement on Mars to “make life multi-planetary.” SpaceX faced repeated rocket failures and nearly ran out of money before finally succeeding with a launch, which led to NASA contracts and long-term success. What explains Musks drive towards almost impossible goals that seem to guarantee failure? I think this quote from Musk provides some insight: “When something is important enough, you do it even if the odds are not in your favour.”

💬 6. Managers Should Give Continuous Feedback: Integrating ongoing conversations, feedback, and recognition (CFRs) with OKRs enhances performance and builds a positive culture.

Chapter 15 Summary

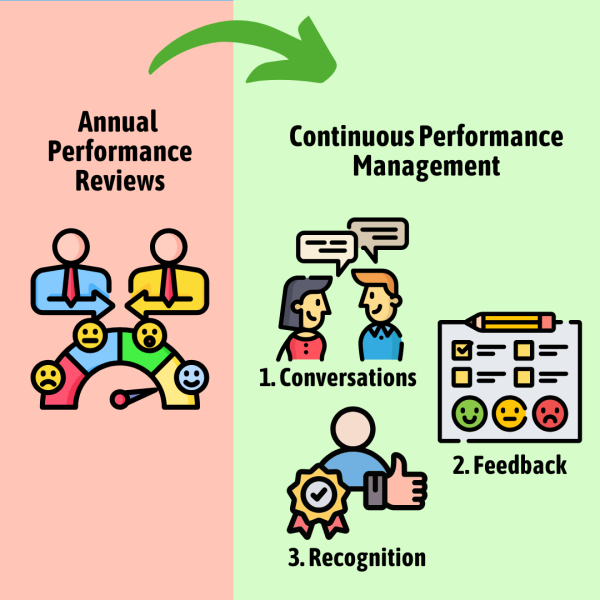

This chapter explains how continuous performance management is a better alternative to outdated annual performance reviews and how it enhances OKRs.

- The Problem with Annual Performance Reviews: Annual reviews are slow and ineffective. They take about 7.5 hours per person, yet only 6% of managers find them valuable. These reviews are often biased, focusing on recent events instead of the bigger picture, and don’t do enough to help employees improve.

- What Is Continuous Performance Management?: Continuous performance management replaces annual reviews with ongoing conversations, feedback, and recognition. It focuses on helping employees grow rather than just judging their past work. Unlike annual reviews, it happens regularly, is mostly separate from compensation (so employees don’t play it safe with OKRs), and emphasizes coaching and improvement instead of simply evaluating results.

- Three Core Elements:

- Conversations: Regular one-on-one meetings are essential. Andy Grove suggested 90-minute one-on-ones every two weeks to build trust and create a coaching relationship. These conversations are about teaching and guiding, not giving orders.

- Feedback: Two-way feedback helps employees and managers grow. Employees learn where they can improve, while managers can ask, “What do you need from me to succeed?” to build collaboration and provide support.

- Recognition: Recognizing achievements tied to OKRs motivates employees and highlights meaningful work. This can include peer-to-peer shoutouts, “achievement of the month” awards, or public mentions at all-hands meetings. Recognition reinforces what matters most to the company and boosts morale.

Chapter 16 Summary

This chapter explains how Adobe replaced outdated annual performance reviews with a continuous Check-In process, boosting employee satisfaction and productivity.

- Annual Reviews Weren’t Working: Adobe’s old system of annual reviews was time-consuming and discouraging. Managers spent 8 hours per employee writing lengthy reports, and employees were often disappointed with their ratings. This created a temporary productivity boost before reviews but led to a spike in employee turnover every February when the reviews were finalized.

- The New Continuous Check-In Process: Executive Donna Morris led the shift to a Check-In process that aligned better with Adobe’s values. Check-Ins allowed employees to adjust priorities quickly, get faster feedback, and stay engaged. These meetings happen at least every 6 weeks and focus on three key areas: quarterly OKRs, feedback, and career goals. To pull this off, they launched an online resource center with video training and role-playing exercises to help managers improve essential skills like giving constructive feedback.

Chapter 17 Summary

This chapter explains how the startup Zume Pizza used OKRs to create clear goals and disciplined management during rapid growth.

- Zume Pizza—A Disruptive Startup: Zume Pizza is changing the pizza industry by baking pizzas on delivery trucks using robots and a high-tech logistics system. While it sounded like a gimmick to some, the company quickly captured 10% of the local market in Silicon Valley, proving its model could work.

- How OKRs Brought Disciplined Management: As Zume expanded from two founders to a diverse team of chefs, engineers, and marketers, OKRs became critical for managing its complex operations. Initially, the OKRs had a top-down approach to ensure alignment and survival. For example, one key objective was to “delight customers,” with measurable key results like a net promoter score of 42 and an average order rating of 4.6. Each employee met with their supervisor every two weeks for one-on-one meetings to create an action plan for the next two weeks. This structure kept the team focused and united as the company grew.

📈 7. Culture Shapes Success: OKRs work best in cultures that value transparency, accountability, and collaboration. They turn shared values into measurable results.

Chapter 18 Summary

This chapter highlights how an organization’s culture is essential for achieving high performance and how OKRs can help shape and reinforce it.

- Why Is Culture Important?: A strong culture makes organizations more efficient. Andy Grove believed that when people share the same values, they act predictably, so there’s less need for rules or constant oversight. Companies like Intel and Google thrive by fostering key cultural traits like transparency, accountability, and a focus on measurable results.

- How OKRs Drive Culture: OKRs help build and maintain a positive culture by making everyone’s goals visible and showing how individual efforts connect to the organization’s bigger mission. At Coursera, for example, President Lila Ibrahim used OKRs to reinforce the company’s core value of “students first.” This value translated into specific key results, such as “increase monthly active users to 150,000,” embedding the company’s core values into its everyday operations.

Chapter 19 Summary

This chapter explains how OKRs helped Lumeris, a healthcare company, build a culture of transparency, accountability, and collaboration.

- Lumeris’ First Failed Attempt at OKRs: When Lumeris first introduced OKRs, the effort failed. Employees simply checked off tasks without understanding the bigger purpose, and many didn’t see how OKRs benefited them. The system looked good on paper but didn’t drive real change.

- How They Made OKRs Work: Lumeris relaunched OKRs with a focus on culture change. Following Jim Collins’ advice to “get the right people on the bus,” the company replaced several top executives who didn’t fit the new culture and replaced 85% of the HR department to improve hiring and remove poor performers. Then all 250 managers were retrained how to set OKRs with their teams, emphasizing “brutal transparency without judgment.” (COO Art Glasgow) Monthly leadership meetings now include reviews of each department’s OKRs—if one department is falling behind their key results, all leaders help brainstorm how they can get back on track, building strong cooperation within the company.

Chapter 20 Summary

This chapter shows how Bono’s ONE Campaign used OKRs to reshape its culture and better connect with African communities.

- The ONE Campaign’s Beginnings: Bono started the ONE Campaign with $1 million in funding from the Gates Foundation. His goal was to use the campaign to create real political change. It achieved major successes, including $100 billion in debt relief for African countries and securing equal access to AIDS drugs, significantly reducing AIDS-related deaths.

- Using OKRs to Drive Culture Change: The ONE Campaign faced criticism from African voices for not being guided by local perspectives. To address this, the campaign used OKRs to drive cultural change. Key results included adding two African board members and building relationships with 10-15 African thought leaders. One of these leaders, Mo Ibrahim, emphasized that corruption, costing Africa $1 trillion annually, was a more urgent issue. This insight led to impactful lobbying efforts, resulting in laws requiring companies in the EU and NYSE to disclose payments for mining rights, promoting transparency and reducing corruption.

Chapter 21 Summary

In this chapter, the author shares a vision for how OKRs can shape a better future.

- OKRs, a Tool For a Brighter Future: John Doerr believes OKRs can inspire the next generation of entrepreneurs, helping them be more productive and innovative. He imagines a world where kids learn OKRs in school alongside reading and math, giving them tools to set goals and achieve more. If everyone used OKRs, society could become much more efficient and creative. The author sees this as just the beginning of the positive impact OKRs can have.

- Set objectives: Write down all goals for the next quarter and circle the top 3 most important ones.

- Define key results: For each goal, list 3-5 specific measurable results with clear numbers or outcomes.

- Mix committed and stretch goals: Set goals you’re confident you can achieve by putting in your best effort, but also include one bold stretch goal to push your limits.

- Start with a pilot: Test OKRs with one small team or project before rolling them out more widely.

- Make OKRs visible: Post OKRs in a shared document, dashboard, or whiteboard for everyone to see.

- Review weekly: Every 1-2 weeks, schedule a one-on-one check-in to track progress, discuss challenges, and adjust goals as needed.

- Celebrate progress: Acknowledge achievements in meetings or emails, even if stretch goals aren’t fully met.

- Reflect and improve: After each 90-day OKR cycle, ask what worked, what didn’t, and how the next cycle can be better.

Community Notes