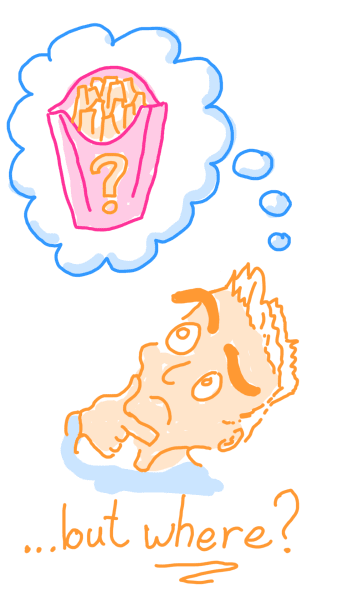

People today are confused about how to eat. You can see this is true just by looking at people in the supermarket, who are trying to decide whether to buy the low-fat item or the low-carb or low-cholesterol or the gluten-free one.

Michael Pollan believes the cause of our confusion is something called “The Omnivore’s Dilemma,” an idea that comes from the scientist Paul Rozin. You see, humans are omnivores, which means we can eat many types of food. This gives us an evolutionary advantage over other animals, because we are never too dependent on one type of food.

But being an omnivore also causes confusion because we must decide for ourselves what foods are safe and good.

Over time, human cultures figured out what is good to eat and passed down this wisdom through traditional cuisines. But today many of us have drifted from our traditions, especially in America. So “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” has emerged again in modern supermarkets and we are again unsure of what to eat.

(In some European countries, people continue to eat like their grandparents did. Ironically, they are often healthier on average than Americans, many of whom follow the latest health trends. This is known as “The French Paradox.” (Encyclopedia.com))

In this book, Michael Pollan set out to ease his own confusion about food by following four different meals, from soil to plate. So he could understand exactly what he was eating and what was its true cost—to his health, other humans, and the planet.

About the Author

Michael Pollan (official website) has written many New York Times bestselling books, mostly about food. He’s also a Professor of Journalism at Berkeley.

🌽 1. Corn is in Everything: Subsidies for corn farming bring us more unhealthy, processed and fast foods

If I ask you to imagine a farm, then you will probably think of: A large red barn, stacks of hay, cows, chickens, and maybe a cat or dog running around.

Maybe that is what a farm looked like 100 years ago, but today it is much different:

- Farmers are less than 2% of the US population, and they grow all the food that the rest of us eat. It’s a much different situation from a century ago, when a quarter of people lived on farms.

- Farms are generally large-scale industrial operations, which means heavy machinery and chemicals and tonnes of synthetic fertilizer.

George Naylor is one farmer interviewed in this book, and he basically just grows field after field of corn. The biggest reason why George and other farmers grow so much corn is because the US government provides huge subsidies for corn over the other crops—basically an extra paycheck.

George sells all his corn to a tall grain elevator nearby, where it is distributed by some of the biggest corporations in the country like Cargill and ADM. (Corporations which helped shape the laws creating the corn subsidies in the first place!)

Corn is by far the #1 crop in America, but very little of it is actually eaten by humans.

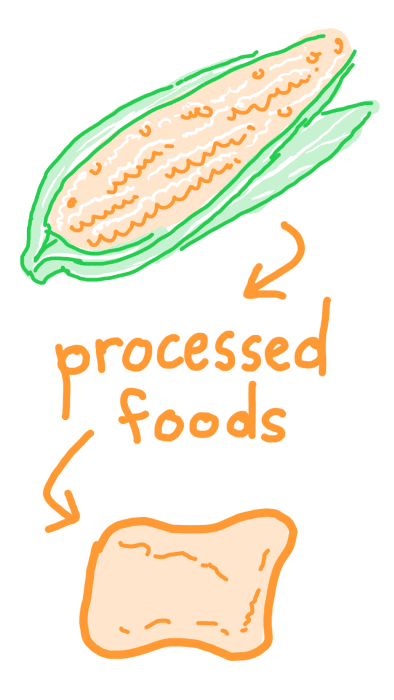

Almost all of America’s corn is fed to animals, turned into ethanol for fuel, or broken down into ingredients for processed foods. This last one is incredibly interesting…

Places called ‘wet mills’ use chemistry to break down corn into building blocks for processed foods. That includes many of the ingredients on food labels that are impossible to pronounce like: high fructose corn syrup, maltodextrin, xantham gum, etc.

This means the rise of unhealthy processed foods was partly caused by the subsidized corn (NPR.org), because it made them cheaper to produce. And cheaper processed food caused an explosion of obesity in America. The author Michael Pollan tells the story of buying a meal from McDonald’s for his family and discovering that every single item contained corn, including:

- The fries (fried in corn oil),

- The drinks (sweetened with corn syrup),

- And even the cheeseburger and chicken nuggets! (because they came from animals mostly fed with corn).

Today less than 2% of people grow all the food, mostly on large-scale industrial farms. Because of subsidies, the most popular crop is corn, which is then fed to animals and broken down into countless ingredients for unhealthy processed foods.

🐄 2. Meat’s Hidden Costs: Industrial feedlots hurt our health, the animals, and the planet

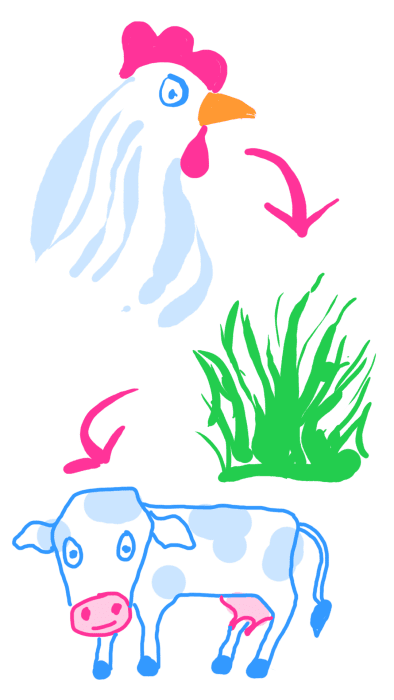

If I ask you to again imagine a farm, this time where cows are raised, then most people would think of a few cows standing on a grassy hill chewing grass. Maybe that is what an animal farm looked like 100 years ago, but not anymore.

Modern animal feedlots are called CAFOs (short for concentrated animal feeding operation). Michael Pollan bought a calf and sent it to a CAFO in Kansas, to fulfill his mission of following meals from farm to plate. What he saw in Kansas was like a mini city with over 30,000 cattle. There were endless rows of cattle standing in mud and faeces and being fed endless amounts of corn.

This setup has many costs:

- Costs to the animals. Cows are ruminant animals, which means they evolved to eat grass. They are fed corn on crowded feedlots because it is cheap and makes them gain weight fast. But those conditions make the cows more vulnerable to diseases and infections, so they need antibiotics and various supplements.

- Costs to the planet. Beside the feedlot, Pollan saw a lake of manure, waste from all the cows that had nowhere to go. All the medications and chemicals used in modern farming also eventually affect the water we drink.

- Costs to our health. Research has found many health advantages to eating grass-fed beef (Heartstone Farm) over grain-fed feed. When cows are fed with grains like corn, their meat contains more saturated fat and less healthy omega 3 fats.

The book Fast Food Nation revealed how large corporations reshaped America’s food systems in pursuit of greater profit. The large slaughterhouses may process 400 cows per hour. That kind of efficiency makes it possible for McDonald’s to sell hamburgers so cheaply, but at the cost of the average person’s health. That book said, “The typical American now consumes approximately three hamburgers and four orders of french fries every week.”

Read more in our summary of Fast Food Nation by Eric Schlosser

Cows are now fed mostly corn on crowded feedlots called CAFOs. These conditions negatively affect the animals (which are designed to eat grass), the planet (because of the additional waste products), and our health (because grain-fed beef is less healthy than grass-fed).

🏭 3. Big Organic: The counter-cultural organic movement has become part of the industrial food system

In 1840, a German scientist named Baron Justus von Liebig discovered that for plants to grow, their soil must contain nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus. This discovery was really the birth of our modern industrial food system because it led to synthetic fertilizers. Today almost all crops are grown with synthetic fertilizers, which contain nutrients produced by chemical reactions.

Science works by breaking everything down into small pieces, then trying to understand what those pieces do. While this approach is often very effective, it can also be dangerous. We begin to assume that what we know is all there is to know, when in reality biology continues to be an unfolding mystery.

The organic movement began in 1940, when Sir Albert Howard wrote An Agricultural Testament. He said the most healthy way to farm was to mimic natural ecological systems as closely as possible.

The organic philosophy was spread to a much larger audience by J. I. Rodale, who published a magazine called Organic Gardening and Farming. It became an important part of the 1960’s counterculture, with many hippies gathering on small communal farms to try organic farming.

Today, organic food sells itself based on that past reputation of small family or community farms. The marketing on the package at Whole Foods tells a compelling story. You will often see beautiful photos on the package of a small farm or happy grazing cows.

But in reality, the organic movement has slowly transformed into “Big Organic,” another wing of the industrial food system:

- The organic milk comes from dairy factories that look about the same as regular ones.

- The organic lettuce is grown in endless fields using huge industrial machinery, just like the regular lettuce.

- The ‘free-range’ chicken often spend their whole lives inside, never taking a step out of the small door required by regulations.

But Michael Pollan concludes the ‘industrial organic’ system is probably still an improvement over the old one. The biggest difference is that the inputs have changed. Crops are grown with manure instead of synthetic fertilizer, and many pesticides are prohibited. Animals are fed with organic corn instead of regular corn, and there are more rules around antibiotics and growth hormones. In the end, the use of less chemicals is probably better for us and the planet.

There’s another book you may like called Why We Sleep, written by a sleep researcher named Matthew Walker. One of the most important points he makes is that our modern world can easily disrupt our sleep patterns, which harms our health. For example, the blue light that comes from electronic devices suppresses your body’s levels of melatonin, a hormone that helps us get to sleep. Walker also wrote, “Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer.”

In 1940, organic farming started as a movement of growing food by copying natural systems. But it slowly grew to become a part of our regular industrial food system. (Keeping some improvements like less pesticides, synthetic fertilizers and chemicals.)

🚜 4. Grass Farming: Some local farmers like Joel Salatin continue to work towards the organic ideals

So, is organic food doomed to be just another flavour offered by our regular industrial food system? Maybe, but maybe not…

Joel Salatin is one farmer who may prove the ‘organic ideals’ are still possible. On his Polyface Farm in Virginia, Joel produces food for local people that is mostly organic and ecologically sustainable. From just 100 open acres, he produces tens of thousands of eggs, thousands of chickens and hundreds of other animals like cattle, pigs and turkeys.

3 chapters in this book were dedicated to Joel Salatin’s farm, which Michael Pollan visited for a few days. Each chapter described one way this farm was different:

- Better Management of the Landscape. Salatin calls himself a “grass farmer” because the food he grows ultimately depends on the grass. Using a technique called “Management Intensive Grazing,” he continuously moves his cows and chickens over the grass. The cows never overeat one area so the grass grows back healthier than ever, and the chickens fertilize the land with their droppings.

- More Humane Treatment of Animals. The animals spend most of their time outside, eating mostly what they were designed to eat. The end result are unmistakably happier animals. The chickens are also slaughtered in the open, where customers can watch if they want to. That transparency results in more ethical meat.

- A Direct Relationship With Customers. Salatin sells food directly to local restaurants and customers, whom he keeps in touch with through direct mail letters. Sure, they like the flavour and the potential health benefits, but it’s also about ‘opting out’ from the industrial food system and ‘the barcode people.’

In the future, will most farms look like Joel Salatin’s? That is difficult to imagine. The biggest problem is that his type of farming is much more complex and work-intensive than an industrial farm. It may not work at a larger scale. But there’s hope those kinds of farms will become a larger part of our food system over time, as more people ‘opt out’.

Joel Salatin’s farm in Virginia copies natural cycles that are sustainable, like using chickens to fertilize the grass that feeds their cows. The animals eat more of what they’re designed to and live more humanely. His customers buy from him directly and share his principles.

🌲 5. Hunting and Gathering: Going into the forest is the oldest way of finding food

In the final part of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Michael Pollan sets out to find all the food he needs for a meal in the wild. That means hunting animals and gathering plants and fungi, like how our ancestors ate for millions of years.

Today we see the Agricultural Revolution as the beginning of modern civilization, and it was. But the historian Yuval Noah Harari says that agriculture actually caused a decrease in well-being for most humans after it was invented.

In his book Sapiens, Harari calls agriculture “history’s biggest fraud.” He says that compared to hunter-gatherers, most early human farmers were less healthy, ate less nutritious food, suffered more diseases and starvation, and worked much longer hours. The humans only continued farming because they mistakenly believed it would provide better security.

Anyway, here are some 5 insights from Michael Pollan’s experiences hunting wild pigs and gathering mushrooms:

- His way of seeing changed immediately. After he decided to gather food, he began to see edible things all around his neighbourhood, including herbs, mushrooms and birds. When he went hunting, his senses seemed to be much sharper, like he could see farther than ever before.

- Hunting looks very different from the outside and the inside. The author is a liberal university professor and journalist. In his circles, hunting is often looked down upon as a way of enjoying killing. But from the inside, he was surprised to find that hunting was deeply enjoyable and downright exhilarating.

- Hunting made him think about the ethics of eating meat. It forces people to be face-to-face with the animal, instead of a sterile supermarket package. So he read a book by Peter Singer, a prominent animals rights activist, and even tried being vegetarian. Ultimately, he did go back to eating meat, but with higher standards about where it came from. (In online reviews of this book, vegans were the least happy about this chapter.)

- Mushrooms make “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” very real. Because they can either be delicious or kill you. But the knowledge about which mushrooms to eat was somehow passed down through human cultures for thousands of years, directly from person to person.

- Wild food inspires gratitude, as if he were receiving a gift. It feels like getting ‘free’ food just for looking around. This way of eating is time-consuming, but it doesn’t carry hidden cost to the health of the planet like a fast food meal.

Gathering mushrooms taught Pollan to see nature differently and taught him the importance of person-to-person knowledge. Hunting wild pigs was surprisingly very enjoyable, but made him think again about veganism.

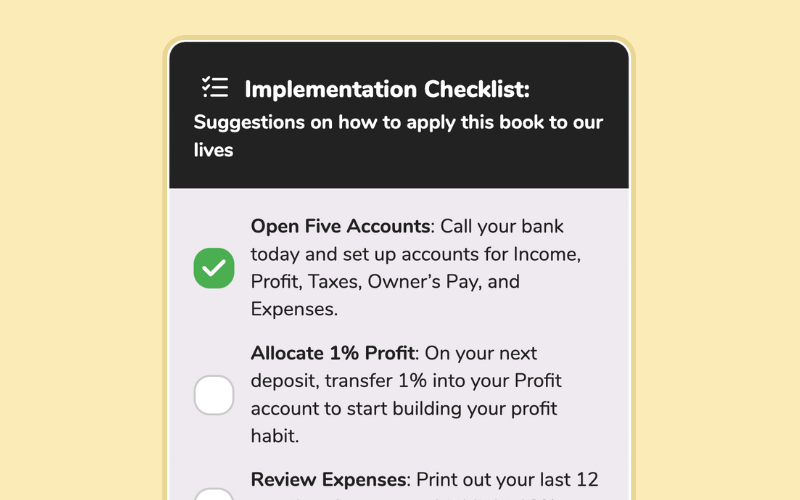

- Check the ingredients label of 5 items in your home. Do a Google search for the ingredients you don’t recognize. How many probably came from corn? This is a great way to better understand what you’re eating and eat more unprocessed whole foods (VeryWellFit.com).

- Look at the organic food next time you’re in the supermarket. I’m sometimes surprised it doesn’t cost much more than regular food. Health experts made a list of a “Dirty Dozen” (EatingWell.com) fruits and vegetables that absorb the most pesticides. These include strawberries, spinach, tomatoes, apples, etc.

- Write down what new way of getting food you’d like to try. It could be gardening, fishing, looking for wild plants, or even hunting. The first step is to clarify your interest, then explore your local options with a Google search or the right book.

Community Notes